Chapter 8 : Running for Our Lives

By Steve Ongerth - From the book, Redwood Uprising: Book 1

Download a free PDF version of this chapter.

“The only reason that I ran for the Board of Supervisors in the first place, primarily, was to support the timber industry”

—Humboldt County District 2 Supervisor Harry Pritchard, 1987

When Maxxam came to Humboldt and bought out old “PL”,

And ripped the worker’s pension fund and turned the land to hell,

Old Bosco sent a press release to say he’d lend a hand,

And he didn’t break his promise—he just lent it to Maxxam.—Lyrics excerpted from Where’s Bosco? By Darryl Cherney, 1988

Darryl Cherney ran for congress,

As a singing candidate,

Some folks said, “he dropped out early”,

Others said, “it was too late”.—Lyrics excerpted from Darryl Cherney’s on a Journey, by Mike Roselle and Claire Greensfelder, 1990

The fallout from EPIC vs. Maxxam I was felt almost immediately. Emboldened by Judge Petersen’s decision, and the revelations that the California Department of Forestry had essentially bullied the Department of Fish & Game into silence on the cumulative impact of logging on wildlife in the THP review process, the latter agency took an unprecedented stand. Led by John Hummel, the DFG filed “non-concurrence” reports on five Humboldt County THPs, including three by Simpson Timber Company, one by Pacific Lumber, and one by an independent landowner. In doing so, Hummel declared:

“The wildlife dependent on the old growth redwood/Douglas fir ecosystem for reproduction, food, and cover have not been given adequate consideration in view of the potential impacts…Our position in Fish and Game is that if clearcuts on old-growth stands are submitted, we will not concur until these issues are resolved.”

He further declared that economically viable alternatives to clearcutting had been proposed or evaluated, and the DFG was considering developing position statements in favor of protecting spotted owls, marbled murrelets, fishers, red-tree voles, Olympic salamanders, Del Norte salamanders, and tailed frogs as “species of special concern” in the THP process. [1]

The CDF remained entrenched and indicated that they would ignore Petersen’s ruling by announcing that they would simply change the rules to benefit Corporate Timber. Following the DFGs “non-concurrence” filings, CDF director Jerry Partain called upon the California Board of Forestry to invoke its emergency powers to allow the CDF discretion to overrule DFG findings and approve THPs anyway. This was also unprecedented. The emergency rules had hitherto only been used to protect the environment; now Partain was calling for the opposite. The CDF director’s action brought immediate condemnation from the Office of Administrative Law, the Planning and Conservation League, and EPIC. Among other things, they charged that this rule change should require a full EIR under CEQA. [2]

No doubt Corporate Timber was the biggest motivator behind Partain’s machinations. Epic vs. Maxxam I threatened to shake the agency’s practices up significantly, and not just in Humboldt County. For example, in Mendocino County, local residents filed challenges to two Louisiana-Pacific THPs in the Navarro and Big River Watersheds. [3] The Corporations’ response was to lobby the BOF to require administrative fees of $1,000 per challenge, a threat to citizen oversight that even some pro-Corporate Timber backers considered overshoot and legally untenable. [4]

* * * * *

It was within this political context that Darryl Cherney’s and Greg King’s campaign for office took place. As the environmentalists’ struggle for forestry reform gained momentum and public support they increasingly found themselves in conflict with the government at all echelons. Whether at the federal, state, or county level, it was scarcely an exaggeration to say that politicians and judges were heavily influenced by Corporate Timber. Maxxam and Simpson called the shots in Humboldt County, Georgia-Pacific controlled Mendocino County to the south, and Louisiana-Pacific was a heavy hitter in both.

Uncritical timber industry supporters dominated the local governments in both Humboldt and Mendocino Counties. In Humboldt the Board of Supervisors was led by Second District supervisor Harold Pritchard and Fifth District supervisor Anna Sparks. Sparks was known for her reflexive opposition to any move to limit corporate power [5], and Pritchard had made it known that he had run to save the interests of (corporate) timber. [6] Meanwhile, in Mendocino County, a solid Corporate Timber bloc—led by reactionary supervisors Marilyn Butcher in District One, Nelson Redding in District Two, and John Cimolino in District Four—reliably cast their votes in the best interests of G-P and L-P. District Three Supervisor Jim Eddie was a moderate, but often cast his vote with the former in many cases, leaving District Five Supervisor Norm de Vall as the lone dissenter. Cimolino, had announced that he would not seek an additional term of office, [7] but one of his potential successors, Republican Jack Azevedo, stood at least as far to the right politically as Butcher and Redding, and he was unapologetic in his stance. There was no doubt with whom he would cast his vote on environmental matters. [8]

At the federal level, Doug Bosco represented California’s First Congressional District, encompassing Santa Rosa all the way north to the Oregon border, covering almost six entire counties, including Sonoma, Mendocino, and Humboldt. The incumbent was a machine Democrat, whose home office was in Sebastopol. [9] According to his critics, Bosco had waffled on the issue of Maxxam’s hostile takeover of Pacific Lumber from its inception in 1985 and by 1988, he had fully endorsed it, dismissing the campaign to oppose the takeover as “an east coast media hype”. Bosco’s support for offshore oil drilling—opposed by many coastal residents of his district across the political spectrum—alienated many of his assumed constituents, including most environmentalists. [10] Darryl Cherney said of the congressman:

“He has positioned himself as an enemy of the people…Bosco said in a recent press release, ‘I remain open to the possibility of a negotiated agreement that would allow for some limited development off central and northern California’…What Bosco calls limited is 150 tracts of oil rigs with additional leasing to open up after the year 2000. Add to this Bosco’s Congressional votes for nerve gas manufacturing, the Trident II missile, a contingency plan for the invasion of Nicaragua, and the financial support for the El Salvadoran death squads, and it becomes quite clear: Doug Bosco is in the pocket of the military industrial complex lock, stock, and oil barrel. [11]

Even more damning, according to several community publications, including The Russian River News, The Anderson Valley Advertiser, and the Country Activist, Bosco had received a series of questionable loans from the Sonoma County based Centennial Savings, which was laundering illegal drug money. [12]

California State Assemblyman Dan Hauser, yet another Democrat serving the First Assembly District, also faced reelection that year. The incumbent had been a guest at a Maxxam sponsored $250 per-plate dinner, and this alone made him a target for a challenge from environmentalists. King said of his opponent:

“Dan Hauser no longer deserves the 1st District Assembly seat. He has sold his constituents down a siltated polluted river, ignoring demands for a clean environment and responsible government. Hauser has become a Willie Brown protégé, snuggling up to uncaring corporations that exploit resources without considering the human and environmental costs. I will not stand for this and next year the voters can choose not to stand for it either.” [13]

Though Willie Brown described himself as a “progressive”, he was rarely actually a friend to the “little guy”, and was quick to reward his corporate campaign donors at every opportunity. In matters of the timber industry, Willie Brown had recently overridden the wishes of the people of Mendocino County by ramming through his bill, AB 2635, which stripped counties of local jurisdiction in regulating aerial herbicide spraying.

Adding to the urgency, 1988 was a Presidential Election year, and historically the contest for the Oval Office usually generates a much higher turnout than lower profile election cycles. This one would be especially significant, because Ronald Reagan was termed out. The closing years of “the Great Communicator’s” term were wracked with scandals, including the Iran-Contra affair, not to mention the Savings & Loan scandals that involved DBL, Boesky, and Maxxam. Reagan’s support for the apartheid regime of South Africa as well as numerous unpopular right-wing governments in the so-called Third World had reawakened a leftist opposition that many had considered dead and buried due to the president’s supposed landslide election in 1980. His stances on the environment, including the choice of Christian Fundamentalist and rabid anti-environmentalist James Watt as secretary of the Interior had galvanized the green movement almost from the get-go. What could have been an easy contest for Reagan’s chosen successor, Vice President George Herbert Walker Bush, suddenly became a dogfight. The interest generated by the main election brought attention to the other contests as well.

Cherney and King decided to challenge the incumbents. Pledging to “take the syrup out of politics”—a somewhat tongue-in-cheek homage to the coincidence that a former child spokesperson for Bosco syrup was now preparing to run against a politician by the same name, Cherney declared his intent to unseat the incumbent in the Democratic Party primary. [14] King similarly announced his goal to unseat Dan Hauser, but since that race was nonpartisan, King ran as a member of the Peace and Freedom Party (P&F), which described itself as “democratic socialist”. [15] Regardless of their affiliations, both candidates sought endorsements from the Democratic, Green, and P&F Parties, but half-jokingly announced that they were actually running as write-in candidates for the newly formed Earth First! Party, whose platform was “150 feet up a redwood with a tree hugger sitting on it.” [16]

There was a marked difference in the presentation of the two campaigns, however. Both King and Cherney were media savvy, of course, but King approached it as a reporter, dealing primarily in facts, whereas Cherney approached it as an entertainer, dealing in spectacle as well as factual information, and history shows that the latter tends to be more conducive to drawing attention to elections in the United States. Also, State Assembly races are almost never featured contests, especially when eclipsed by higher profile campaigns. As a result, King’s campaign never amounted to much, although he did show up for some campaign events and a couple of press conferences, his campaign was nearly invisible relative to Darryl Cherney’s. [17] Cherney, on the other hand, was very visible in his run for office. He ran, quite literally, as a singing candidate, and though he considered his chances of winning remote, he pledged to bring his guitar with him “right into the halls of Congress, strumming and crooning (his) testimony on all sorts of issues that urgently need to be addressed.” [18] For his campaign, the already prolific Earth First! troubadour, who was rapidly becoming the “Joe Hill” of the Earth First! movement, penned a new song, Where’s Bosco? which took the incumbent congressman to task for his unwillingness to be accountable to the public for his failures and included the refrain, “Don’t call me a radical, Bosco’s underground!” [19]

Cherney’s wasn’t alone in his quest to challenge Bosco from the left. Two other disgruntled Bosco constituents, Neil Sinclair and Lionel Gambill, both Democrats, decided independently of Cherney and each other, to challenge Bosco in the primary. [20] Ironically, though neither challenger was aware of the other, both of them lived less than ten miles apart, at opposite ends of the Bohemian Highway in the rural southwestern Sonoma County, near Greg King’s home town. Sinclair hailed from Monte Rio, on the Russian River, near Cazadero and Guerneville, and Gambill lived in Occidental to the south. Although Cherney had declared his candidacy first, he hadn’t actually officially filed the necessary paperwork until after the other two had done so, even though neither candidate contacted Cherney to confirm the seriousness of his intent. Cherney ruefully reflected that had he known about either competing candidate, he would have kept the $900 he spent on his filing fee, stepped aside, and supported the stronger of the other two challengers. [21] Adding to Bosco’s challenges from the left, Eric Fried, a self described socialist and supporter of both Earth First! and the timber workers ran on the Peace and Freedom ticket.

The Earth First! candidate nevertheless accepted the additional contenders as potential allies, because the goal of his campaign was to unseat Bosco and draw attention to Maxxam’s pillage of the Humboldt redwoods. Cherney initially had no opinion of Neil Sinclair, as he knew almost nothing about him. On the other hand, his impression of Lionel Gambill was quite positive, and the latter was, in Cherney’s opinion, “a respectable looking sixty-year-old candidate.” Attempting to make lemonade out of lemons, Cherney suggested (to both Gambill and Sinclair) that if each candidate split the vote roughly equally in the winner-take-all primary, all they had to do is get Bosco to receive one percent less than any of the others. At the very least, the three of them together could render Bosco politically impotent by ensuring that he received less than 50 percent of the popular vote. Cherney even supported Gambill when the Sierra Club’s Sonoma County Chapter elected to endorse Doug Bosco (perhaps out of the timid belief that Bosco was the best choice to fend off an even worse Republican challenger in the November general election). Gambill attempted to address the meeting, but was essentially ignored. Cherney attended this particular meeting, spoke in support of Gambill, and sang a quickly written song called I Dreamed I Saw John Muir Last Night. [22]

Right away, Cherney’s and King’s candidacies induced critics to stir up animosity, especially in light of some of the more controversial statements made by Dave Foreman and Ed Abbey, but those statements were eclipsed by a far more acrimonious statement made by another Earth First!er. A column penned in the Beltane (May 1) 1987 edition of the Earth First! Journal, written by “Miss Ann Thropy”, implied that, following the logic of Malthus, AIDS and other fatal diseases were nature’s way of regulating the human population, and concluded “if the AIDS epidemic didn’t exist, radical ecologists would have to invent one.” [23] Miss Ann Thropy was an obvious nomme de plume, and many assumed it was Dave Foreman, though it was later revealed to be, by his own admission, fellow Earth First!er Chris Manes. Manes claimed that the column was “dark humor”, but he was deadly serious about the thinking behind it, declaring,

“Some Earth First!ers have suggested in Malthusian fashion that the appearance of famine in Africa and of plague in the form of AIDS is the inevitable outcome of humanity’s inability to conform its numbers to ecological limits. This contention hit a nerve with the humanist critics of radical environmentalism, who contend that social problems are the cause behind world hunger and that suggesting plague is a solution to overpopulation is ‘misanthropic.’ They have also produced a large body of literature attempting (sic) to show that Thomas Malthus was incorrect about the relationship between population and food reduction. Malthus may (sic) have been incorrect, famine may (sic) be based on social inequalities, plagues may (sic) be an undesirable way to control population—but the point remains that unless something is done to slow and reverse human population growth these contentions will soon become moot.” [24]

To his credit, Cherney responded to Corporate Timber’s attempts to associate him with the statements made by Abbey, Foreman, and Manes, refuting the notion that Earth First! in general, or he and King, specifically, held such positions. [25] Nevertheless, the Malthusian stances taken by Manes, Foreman, and Abbey were fodder for Cherney’s and King’s critics on the North Coast. For example, Cherney’s and King’s stance on water—which was not Malthusian, but proposed local self sufficiency—raised the ire of North Coast News columnist Nancy Barth. In her column, Barth sounded the alarm about “Ecofascism!”:

Mr. King and Mr. Cherney must certainly realize that use of ground water from wells causes a temporary reduction of the water table. Will they require all rural residents to depend on surface water exclusively, collect rainwater, or face deportation? Will Mr. King and Mr. Cherney and their Earth First! cohorts sit in judgment to determine who has damaged the environment and thus be deported? [26]

Cherney offered a quick response, stating,

The real question is ‘who will Nancy Barth throw out of our area in order to allow more businesses and residents in?’ While human beings are getting mud out of their faucets, Nancy is calling those who call for growth limitations fascists. And if Nancy bothered to read a newspaper every now and then, she would learn that over 60 percent of Santa Rosa wants limited growth. Are they fascists, too? [27]

Cherney also pointed out that Barth’s rejection of Earth First!, ostensibly in favor of “working responsibly” within the system had been tried and found wanting. He reiterated that one of the primary reasons for the existence of radical movements like Earth First! was that environmental groups that adopted moderate stances had hitherto been unable to accomplish any of their goals, until and unless more radical environmentalists had pushed the envelope thus making the former’s positions appear more politically palatable. Barth’s dismissals were typical of most of the critics. In fact, Cherney’s and King’s actual platform was solidly social democratic by early 21st Century standards, and placed them well to the left of the Democratic Party politically.

Both candidates took strong stands on environmental matters, including water (as previously mentioned); timber (sustained yield, uneven-aged management with no old growth harvesting, and restaffing the CDF with trained environmental experts); total opposition to offshore oil; sustainable fisheries; agriculture (a ban on petro-chemicals, synthetic fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides and replacing large scale agribusiness with small-scale organic farms); transportation (incentives for bicyclists and pedestrians, the establishment of auto-free zones, and vastly increased mass transit resources); energy (phasing out nuclear fission power and investment in a crash program to rapidly develop and deploy solar and wind power as well as immediately reducing fossil fuel consumption by implementing mandatory conservation measures); waste (recycling of all waste—which, they argued, would create jobs); and interior (reclamation of wilderness, massive tree planting, stream restoration, and the banning of motor vehicles from national parks). [28]

Their stances on social issues were no less progressive. On matters of “law and order” they advocated focusing on corporate criminals as opposed to petty crimes, and an end to highly unproductive new prison construction. On unemployment, they called for a jobs program geared primarily towards ecological restoration. They called for legalization of marijuana, with rigid environmental standards to prevent its production becoming unsustainable itself. As for their economic perspective, both proposed vigorous prosecution of public trust violations in opposition to corporate power. [29]

Additionally, Cherney called for a massive reduction to the military budget, abolition of all nuclear weapons, redeploying the military to deal with long term ecological restoration projects, and banning of non-essential imports and local self sufficiency. Cherney’s geopolitical stances placed him in opposition to the Reagan dominated Cold War orientation of the United States. Cherney referred to the USSR as “our competitor, not our enemy”, and decried the ideologies of both superpowers, “since neither one worked.” Demonstrating that he was not a racist, Cherney called for the immediate recognition of the Nelson Mandela-led African National Congress as the bona fide government of South Africa and reparations for the then oppressed black population under Apartheid. On the matter of Nicaragua, he called for an end to funding of the Contras. Cherney also proposed a well funded education program and incentives to lower population growth by making it the norm for families to have one child only. [30] In no instance did Cherney take any stance that placed himself on the political right, and in no case did he adopt any of the stances taken by either Dave Foreman or Edward Abbey that had unfairly earned Earth First! the reputation as a politically reactionary movement.

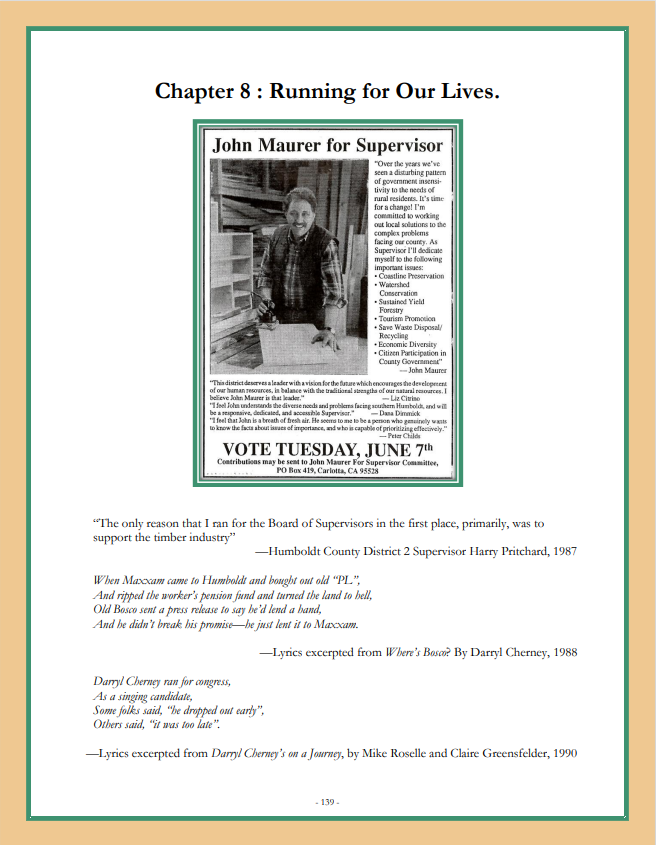

Cherney and King were not alone in their quest to unseat Corporate Timber friendly incumbents. John Maurer and Don Nelson had announced candidacies of their own for the Humboldt County District 2 and Mendocino County District 4 supervisorial elections. Maurer declared his campaign in February of 1988. [31] Pritchard’s seat represented the southeastern-most section out of five districts and included much of the land owned by Pacific Lumber. [32] Don Nelson declared his candidacy on January 20, 1988. [33] District 4 encompassed the northwestern corner of Mendocino County and included the southern portion of the Sinkyone Wilderness as well as Fort Bragg, where the big G-P Mill was located. Given the sensitivity of the issues, Cherney and King agreed to keep their campaigns independent of Maurer’s and Nelson’s and vice versa (and the latter ran their campaigns more or less independent of each other). Cherney and King stressed that they didn’t necessarily endorse Maurer and Nelson (and vice versa), but all agreed that they had roughly similar concerns. [34]

Don Nelson, born and raised on the Mendocino Coast, billed himself as “the workers’ candidate” (and, at least relative to the lame duck Cimolino, that was true enough). Nelson had worked for 20 years in the woods as a logger and timber faller, but for the thirteen years prior to his announcement, he had served as the full-time, paid Business Representative for the Fort Bragg IWA Local. [35] On the other hand, he had opposed the environmentalists’ fight to preserve Sally Bell Grove in the Sinkyone, though he ultimately agreed to a compromise that included some concessions that the IWA accepted. [36] In spite of this, many residents of the county, including a large number of environmentalists agreed that he would be a vast improvement over John Cimolino, and certainly a far superior choice than the rabidly right wing Azevedo. [37]

Meanwhile, both Maurer and his opponent, Pritchard, agreed that timber was the economic lifeblood of Humboldt County, but they had substantially different perspectives on how to ensure the long term viability of it. Pritchard, of course, followed the neoclassical economic rhetoric put forth by Ronald Reagan of “reduced taxes and less ‘burdensome’ regulations will result in a stronger economy.” [38] The incumbent had already served three terms as the supervisor for the Second District, and he was usually 100 percent in agreement with the practices of Maxxam. [39] His stance on clearcutting and the increased harvesting rates by the new P-L was to praise it, declaring, “Those people that are hollering (about sustained yield) don’t know what they are talking about. Today, there’s more wood being grown in the county than is being harvested,” and claimed that P-L’s construction of new infrastructure (though he conveniently omitted that it was done with nonunion labor from out of the county), including dry kilns in Fortuna and Redway as well as a cogeneration plant in Scotia was “proof” that P-L wasn’t “spending that kind of money to go out of businesses.” [40] But, Pritchard was on record as misrepresenting the level of Maxxam’s overcut, claiming that the rate of increase was a mere 3 percent when it was in fact at least 200 percent. [41] Also, he had, in his capacity of head of the regional air quality management district the previous year, sided with L-P and Simpson on air pollution complaints against the two corporations brought to the board by Humboldt County residents. [42]

Maurer’s positions were hardly radical, but they stood in stark contrast to those of his opponent. He considered Maxxam’s takeover of P-L to be one of the most serious threats to befall Humboldt County. “Gone (were) the days of prudent, selective timber harvesting that ensured economic stability.” [43] Despite his resignation, Maurer continued to fight the Maxxam takeover. He started a custom cabinet making and woodworking business, in which he pledged to use sustainable resources. He was one of the plaintiffs in a suit against Maxxam, charging impropriety in the $35 million depletion of the workers’ pension fund. Maurer believed that economic diversity and community growth must be encouraged and maintained, but that resources should be controlled locally. He believed that local manufacturing, including local processing of timber, was infinitely more desirable than raw log exports and clearcutting. Instead of shipping raw logs away, Maurer envisioned shipping quality wood products, such as milled doors and cabinets. His vision was not entirely motivated by self interest or limited to timber, because he also envisioned enhancing other local Humboldt County industries, such as dairy and tourism. [44] Maurer challenged the incumbent on his uncritical stances on Maxxam, arguing that they had taken Hurwitz and Campbell at their word, even though access to accurate information was restricted. “We have every right to expect our supervisors to take a stand on this. The board should be interested in pursuing information so that we as a community can be assured that sustained yield is the case—assurance for long term timber jobs. The future of Humboldt County is at stake.” Additionally, Maurer challenged Pritchard’s accessibility to the public (along with the rest of the board), a claim which Pritchard disputed. [45]

For his part, Don Nelson was anything but a perfect candidate to challenge Corporate Timber in many respects. Nelson had already lost much credibility with the rank and file members of IWA Local #3-469, and the candidate had an inconsistent—and sometimes contradictory—record on forest issues. Nelson had supported the Greens in their joint pickets of L-P over herbicide spraying three years previously, though there was more than a hint of political opportunism in this move. He supported tougher timber cutting regulations [46], including AB 3601, proposed by Assemblyman Byron Sher, which would have limited old growth cutting, at least on paper. [47] He certainly had come out vehemently against Maxxam’s takeover of Pacific Lumber—going so far as to consent to Earth First! quoting him in their publications on the issue. [48] Nevertheless, he felt that individual citizens being able to directly challenge THPs created unintended consequences that represented a potential threat to timber workers’ livelihoods and preferred an intermediary board to address such conflicts. [49] Nelson’s most troubling stance was on clearcutting, which he supported, albeit on a much smaller scale than was typically practiced by Corporate Timber. [50] Nelson defended his position ostensibly on matters of workers’ safety, arguing that selective cutting involved some inherent dangers to workers not likewise extant in clearcutting (such as “widowmakers”), but he parroted dubious industry talking points (that the practice could be sustainable) in defense of it. [51]

Nelson’s peripheral political activity was cause for some concern as well. He was a registered Democrat, active in local party politics, serving on the local County Central Committee. He had also served on the Mendocino County Private Industry Council as well as the Mendocino County Overall Economic Development Plan Committee, which certainly gave him connections and knowledge of County affairs. [52] However, all of his political activity severely limited the amount of time he devoted to bread and butter union issues, which was a growing bone of contention among the rank and file of his union. [53] Nelson supported Jesse Jackson’s run for the Democratic Party nomination, partly due to the latter’s support of the IWA in a labor dispute with timber corporation Champion International in Newberg, South Carolina. [54] However, Nelson and his IWA local also endorsed Doug Bosco over the congressman’s opponents. [55] Nelson defended his inconsistencies as the art of being a negotiator and forging deals between divergent factions, and he cited his experience as a union representative as evidence, but such “negotiations” were usually in the service of making deals with the boss. [56] When the chips were down, Don Nelson was a typical politician and a quintessential machine Democrat.

Despite Nelson’s shortcomings, the consensus opinion among Mendocino County environmentalists was that he represented the best candidate to replace the thoroughly conservative Cimolino. Nelson’s endorsers among the local green community included his son, Crawdad Nelson, (a former G-P millworker turned Earth First!er) [57], Beth Bosk, (who published the New Settler Interview, which was often the voice of the local back-to-the-land community). [58] Nelson co-hosted a weekly labor oriented radio program on local station KMFB in Fort Bragg with Roanne Withers, who also supported his campaign, even though she had endorsed Lionel Gambill over Bosco. [59]

Nelson’s primary challenger, Liz Henry, was slightly more progressive on many issues, though much less experienced, and perhaps too quick to align herself with the Chamber of Commerce on coastal development, an anathema to most local greens. [60] Liz Henry’s husband, Norm Henry, was a registered professional forester with the California Department of Forestry, and had a more or less conventional view on logging (taking the current corporate driven boom and bust system as a given) but Liz was fairly strong on forest preservation issues. [61] Complicating matters further, IWA Local #3-469 and Don Nelson endorsed Mendocino County Measure B, also endorsed by most local environmentalists, which proposed significantly tougher timber harvest regulations [62], and challenged G-P to a debate when the latter claimed that the measure would threaten jobs; G-P declined. [63] It was by no means an easy choice for the environmental community to decide between Nelson and Henry, but all agreed that either candidate was a far superior alternative to Azevedo.

* * * * *

Cherney’s and King’s run for office by no means took energy away from Earth First!’s campaign of direct actions against Maxxam or the other Corporate Timber giants; indeed the actions and the election campaigns dovetailed fairly well, at least in matters of raising public awareness. The two launched their campaigns in Earth First! style by crashing a political function organized by Dan Hauser and then-Speaker of the California State Assembly, Willie Brown, at the Mendocino Hotel on December 7, 1987. The hotel was notorious for class discrimination, having a virtual caste system where housekeeping employees were not even allowed to enter the building through its main entrance. Cherney argued, “That Hauser and Brown would meet in such a ‘den of inequity’ is an insult to all working people!” [64]

One month later, Darryl Cherney took part in a protest in the Big Apple at the New York Stock Exchange. About 20 demonstrators gathered for a lunchtime demonstration on January 13, 1988. The group picketed the building, carrying banners with slogans that included “Wall Street Out of the Wilderness” and “The Real Crash: Deforestation”. Some of the signs were attached to discarded Christmas trees symbolizing Maxxam’s callous use of the forests. Cherney described the mood of the passersby as curious. However John Campbell, speaking for Pacific Lumber from Scotia retorted, “I personally don’t think it will have any effect,” and went on to accuse the demonstrators of putting environmental concerns ahead of human issues. [65]

North Coast Earth First! then unveiled its Headwaters Forest Complex Proposal. [66] The proposal was actually the project of two Humboldt State University forestry students, Earth First!ers Larry Evans and Todd Swarthout. It called for acquisition and preservation of 98,000 acres of wilderness areas in Humboldt County, 31,000 of which were part of the Pacific Lumber holdings, a 3,000 acre Headwaters Forest preserve, and protection of south Humboldt Bay, Table Bluff, most of the Eel River Delta through voluntary conservation easements. [67] The project still allowed for sustainable logging in other areas, and it earned the support of mainstream environmentalists, including the Redwood Chapter of the Sierra Club, whose chair, Jim Owens urged the state’s regional organization to support it as well, declaring, “These measures are essential to fight Maxxam’s clearcutting of PALCO’s old growth.” As was to be expected, Maxxam, along with other timber companies, who stood to lose access to a huge source of potential short term revenue, opposed the measure, claiming that it would result in layoffs and possible permanent loss of jobs. [68] Similar claims had been made by Corporate Timber, especially GP and LP, about Redwood Regional Park, but had never come to pass. [69] The Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance—no doubt speaking the thoughts of Maxxam and other corporate interests—editorialized against the proposal opining:

“Humboldt County is already awash in county and federal parks: another Redwood National Park-type plot of land taken off the tax rolls to supply the needs of a few hundred backpackers is certainly not needed at a time when the county is scrapping for funds to support needed services. Besides, no clear method of acquiring the 96,000 acres was mentioned—or who would pay for it.” [70]

Earth First!’s proposal both drew attention to, and drew fire away from, Proposition 70, the Wildlife, Coastal and Parkland Conservation Bond Act. The $776 bond measure, sponsored by veterans of the decade-long struggle to preserve the Sinkyone, proposed allocating money to various counties for park improvements and wilderness preservation efforts. [71] In Humboldt County, specifically, the measure would allocate $197,000 to the County itself, $27,000 to Fortuna, $20,000 to Ferndale, $20,000 to Rio Dell, and $20,000 to the Rohner Regional Park District. The money would be reserved for development, rehabilitation, restoration, or acquisition of parks, beaches, wildlife habitat, or recreation depending on the situation. The funds would mostly be spent by various departments of parks and recreation, the State Wildlife Conservation Board, and the State Coastal Conservancy. Portions of the funds would then be funneled to various nonprofit groups where appropriate, such as the Sanctuary Forest group of Southern Humboldt, which was slated to receive $4 million for the preservation of land owned by Eel River Sawmills near Whitethorn. [72]

The measure’s supporters included environmentalists, naturally, and even though it had nothing to do with Earth First!’s Headwaters Forest Wilderness Complex proposal, many of the same environmentalists that supported the latter also supported Proposition 70. Country Activist coeditor and EPIC spokesman Bob Martel declared:

“We’re definitely for it. It means the area we call Sanctuary will be preserved. It’s a critical area. We look forward to it passing. It’s the first time in a long time the people have put a bond measure on the ballot, and we think it reflects the attitude of the country, which is three-to-one for preserving old-growth.” [73]

Like the Headwaters proposal, Proposition 70 was opposed primarily by Corporate Timber as well as Corporate Agribusiness. In Humboldt County, Pacific Lumber, Eel River Sawmills, the California Farm Bureau, and the Cattlemen’s Association led the opposition, and often—for the sake of defeating both measures—they conflated the two. These interests framed their opposition as challenging government “land grabs” (which was ironic given the origins of their current holdings) opposing a wasteful boondoggle, and the removal of lands from productive usage. [74] Harold Pritchard opposed both Earth First!’s Headwaters proposal and Proposition 70 vehemently to the point of running ads against them as part of his reelection campaign. [75] However, like the Headwaters proposal, the likelihood was that the long term yield from more sustainable practices—as opposed to short term profit—would be greater, though of course this didn’t serve the interests of the capitalist class. Furthermore, Proposition 70 supporter Rex Rathburn of Petrolia, a member of the group Californians for Parks and Wildlife, pointed out that the land acquisitions covered under the initiative could only come from a willing seller. There were no calls for the use of eminent domain in the measure. [76]

Among the reasons given by Pacific Lumber as arguments against the necessity of either the Headwaters Wilderness Complex proposal and Proposition 70, is that it replanted new trees each time they logged the old ones. What they neglected to mention is that such efforts were rarely—if ever—effective. In response, on March 6, 1988, accompanied by NBC National News, 17 Earth First!ers marched onto Pacific Lumber land and planted 400 redwood and Douglas fir saplings in a clearcut near All Species Grove “to show Maxxam how to get it right.” They were met by Carl Anderson and P-L security who escorted the Earth First!ers and reporters off the property, but made no arrests. [77] In retaliation Pacific Lumber attempted to sue the activists for damages on March 30. [78] The company admitted that they lost no money from the action, but they asked the courts to bar Cherney and fourteen “John and Jane Does” from trespassing on the company’s land anyway, claiming that this was necessary to prevent potential protesters from suing the company should they be injured while on private property. [79] This was rather dubious logic, and it was more likely that Maxxam was primarily interested in controlling the message. [80] Unfazed, Darryl Cherney replied, “I am actually quite happy to be sued by Maxxam. Now the voters will know where I stand.” [81] He further boasted that he safely say that he was the only candidate currently running who had been sued for planting trees. [82]

A week later, the CDF granted P-L permission to log two sites in All Species Grove, and EPIC sued to stop them. Judge Buffington delayed issuing a TRO, and in response, Darryl Cherney declared that of the former didn’t issue a ruling by April 12, he would trespass on P-L land again the next day and serenade the loggers. [83] In anticipation of the protest, three Earth First!ers conducted another tree sit, in All Species Grove. Unfortunately, this effort garnered insufficient media attention, so Greg King decided to organize yet another tree sit in a much more noticeable location, in this case, between a pair of redwood trees straddling US 101 in Humboldt Redwoods State Park. The second crew hung a traverse line and a 20 x 50 foot banner reading “SAVE PRIMEVAL FOREST – AXE MAXXAM – EARTH FIRST!” across the roadway, and King traversed the line waiting for a fellow activist photographer to arrive to take a picture for the local press. King’s support crew then concealed themselves in the dense forest reserve away from the roadway. [84]

The tree sit was primarily intended as little more than a photo-op, but it quickly evolved into a near melee. King’s photographer ran late, and so the activist hung in midair waving to the passing motorists, some of whom honked in sympathy while others returned King’s friendly waves with middle finger gestures. When a passing California Highway Patrol officer arrived and demanded that King stand down and lower the banner, the Earth First!er (whose support crew waited hidden nearby) responded that he could not, because doing so was a two person job. A second CHP officer arrived, followed by a CalTrans service truck, but instead of attempting to arrest and detain King, they simply waited. For whom was not readily apparent, but in time, Climber Dan Collings arrived in his pickup truck and, unlike his earlier cordial but adversarial standoff with King, this time he was not so forgiving. He emerged from his vehicle cussing wildly at King, declaring,

“You fucking Earth First!ers wouldn’t know old growth redwoods if they fell on you! Your goddamned propaganda has gone too far! You get your faces in the newspaper and play God with my job while people like me do the real work and pay for your goddamned welfare checks!” [85]

The climber then ascended about halfway up one of the pair of trees from which the banner hung, faster than any Earth First!er had ever done and—at this point—gestured with his knife as if he intended to cut down King’s traverse line. “You’d better stay away from my traverse line. If you cut that, I may wind up splattered all over somebody’s vehicle below!” shouted King.

“Stop your fucking sniveling! I can cut that banner down without so much as putting a nick in your damn lifeline, and that banner is going! I’ve had it up to HERE with all of your fucking propaganda!” countered Collings, who continued his rapid ascent up the tree.

“Is he with you?” shouted the CHP officer to King through his bullhorn, gesturing towards the climber.

“I don’t know him,” responded King, “but I think he might cut my lifeline!”

At this point the officer sped over to the tree being climbed by Collings and ordered the latter to halt or face arrest. Begrudgingly, the climber halted his ascent, shouting, “Unlike you fucking Earth First!ers, I have a real job and cannot afford to get arrested. There’s no welfare taking care of me!”

By now, the photographer finally showed up, and snapped his photo, and King stood down voluntarily. The CHP cited him for illegally hanging a sign on a federal highway, but he was released without bail, and the photographs ran in numerous local periodicals the next day as well as a major magazine soon after that. [86]

Bolstered by this occurrence, the next day 75 demonstrators, 40 of whom were willing to risk arrest, assembled as promised. The Earth First!ers split into four separate groups and entered the All Species Grove from four different directions. [87] Those that reached the grove dialogued with loggers and some of them attempted to halt a logging truck before being arrested by Humboldt County sheriffs. Others weren’t as lucky. At least 31 of them were thwarted from reaching the logging site, when Humboldt County sheriffs spotted them on adjoining land and asked them to disperse, which they did. 30 more were escorted from P-L land upon being discovered. [88] Darryl Cherney did indeed attempt to serenade the loggers with his signature song, “We Are We Gonna Work When the Trees Are Gone?”, but he was arrested before he could complete it. [89] Before he began, some loggers accused him of being on welfare, a charge Cherney denied. Even though he was interrupted and denigrated, the activist declared, “We were able to offer our opinions to those falling the trees, and even if they don’t agree with us, they know that there are people who care about cutting old growth redwoods.” [90] The action was successful in two other regards: there was no violence, and in spite of the arrests, enough demonstrators had reached the site to halt logging for the day. [91]

* * * * *

At this point, rumors grew that Hurwitz was engaged in yet another shady takeover attempt and he was using Pacific Lumber as collateral. The rumblings began when the company’s debt rating was downgraded by Standard & Poor first to “B-minus”, followed by “triple-C.” Prior to the Maxxam takeover, its rating had been “A-plus”. Maxxam had recently merged with its cash-poor subsidiary, MCO, but the change indicated other activity. [92] The debt rating agency declared that the change “(reflected) the perceived need, ability, and willingness of management to upstream cash from Maxxam to its parent company holdings.” In a press release issued on April 4, 1988, John Campbell declared that Pacific Lumber had strict “covenants” in place to restrict its ability to pay cash dividends to Maxxam. [93]

Evidently these “covenants” mattered little. As it turned out Hurwitz was using cash diverted from Pacific Lumber in yet another suspicious takeover attempt. This time, in a development eerily similar to the folding of Pacific Lumber’s old guard, Kaiser Aluminum’s board of directors accepted a $871.9 million leveraged buyout bid from Maxxam. Essentially demonstrating that Hurwitz lacked any concrete knowledge of the aluminum business and was purely concerned about quick profits, he retained the top executives to help him run the company promising them 15 percent ownership. And, following the pattern of the takeover at P-L, Maxxam hinted they might sell some of Kaiser’s aluminum operations in West Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana, as well as an electrical products line and various real estate holdings. After Maxxam’s acquisition, Kaiser’s debt doubled to over $1.5 billion. In the September 1988 quarterly report filed by Pacific Lumber, the company admitted that Maxxam did indeed use $24.5 million from its forest products division to take over the then 57-year-old company. [94] It was a case of déjà vu all over again.

* * * * *

In spite of these developments, the tide of public and legal opposition continued to rise against Hurwitz and Maxxam still further. Less than a week after the tree sits and trespass, in a stunningly unprecedented move, CDF director Jerry Partain denied three THPs, including two filed by Pacific Lumber on the grounds that P-L had failed to consider the cumulative impacts of their proposed timber harvest on the area’s wildlife. The two THPs included the Shaw Creek cut opposed by Concerned Earth Scientist Researchers and the Lawrence Creek cut. Up to 100 acres from both THP were slated for clearcutting according to Ross Johnson. P-L officials issued a written statement a few days letter expressing their surprise at the decision, arguing that the THPs included all of the information required by the Board of Forestry under Z’berg Nejedley, or at least required according to then past practices. Indeed, Partain was not known for being anything but sympathetic to Corporate Timber, and the company suspected that his apparent change of heart had more to do with political and legal pressure than anything else. Seeming to confirm this suspicion, Ross Johnson declared, “Because we’ve had so many lawsuits, we’re being more thorough in our review of these timber harvest plans. I guess you could give credit to these environmental groups. If we keep getting beat up on, we’ll continue to do a better job.” [95] It was more accurate to ascribe Partain’s change of position to legal pressure, however, because, as the CDF director so bluntly pointed out, “If we did not act on the advice of Fish and Game, we would be in a very weak position to defend ourselves in court.” [96]

That wasn’t to be the last of it, because on April 25, Judge Buffington finally issued a TRO order against further logging in All Species Grove, though by that time, too much damage had already been done. In a later visit to the contested site, Earth First!ers discovered huge pieces of broken logs strewn about a nearly vertical eroded slope as well as a brand new road cut into the north bank of All Species Creek. Pacific Lumber had instead begun a new 263-acre clearcut adjacent to one just halted by the TRO. On April 28, various Earth First! chapters in Redwood Country and the EF! Nomadic Action Group offered a $1,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of Charles Hurwitz for its corporate crimes and crimes against nature. Then, on May 5, in a clear case of legal sleight of hand, P-L requested permission from the court to remove all of the trees they had already cut prior to the TRO, and—naturally—to facilitate that, they would need to cut down old growth trees that just happened to “be in the way”. At the very least, the so-called wheels of justice turned in favor of Earth First! at least in one instance that day, as the near dozen activists facing charges from the May 1987 Week of Outrage received plea-bargain sentences of required community service as well as injunctions against entering P-L property. Also, no charges were ever filed against the arrestees in the recent All Species Grove actions. [97] Although EPIC’s and Earth First!’s had only been partially successful, the potential for them to build upon them was evident. Pacific Lumber was already organizing its response.

[1] “Fish & Game Axes Clearcuts”, EcoNews, January 1988.

[2] “New Ideas for Old Growth”, by Andy Alm, EcoNews, March 1988.

[3] “Battles Rage Over Old Growth”, by Andy Alm, EcoNews, April 1988.

[4] “Newspeak”, by Tim McKay, EcoNews, June 1988.

[5] “Labor, Activists Unite to Fight L-P”, by Crawdad Nelson, Anderson Valley Advertiser, January 10, 1990.

[6] “John Maurer’s Candidate Statement for Humboldt County Supervisor”, by John Maurer, Country Activist, May 1988.

[7] “Cimolino Won’t Run Again”, by Randy Foster, Ukiah Daily Journal, May 10, 1987.

[8] “Azevedo’s List Entries Meet”, by Mitch Clogg, Mendocino Country, November 1, 1988; “Publisher’s Corner”, by Harry Blythe, Mendocino Commentary, November 17, 1988; and “Lisa Henry on her 22nd Birthday”, Interview by Beth Bosk, New Settler Interview, January 1991.

[9] “Vote Lionel Gambill into Congress”, by Darryl Cherney, New Settler Interview, issue #31, May 1988.

[10] “Darryl Cherney: a Conversation with a Remarkable Candidate”, by Michael Koepf, Anderson Valley Advertiser, (in two parts) April 27 and May 4, 1988.

[11] “Confessions of a Candidate”, by Darryl Cherney, Country Activist, March 1988.

[12] See, for example, “Boscogate: an Update”, by Stephen Pizzo, Russian River News, reprinted in the Anderson Valley Advertiser, June 4, 1986.

[13] “Earth First! Runs for Office”, by Darryl Cherney and Greg King, Country Activist, December 1987 and Mendocino Commentary, December 17, 1987

[14] “Darryl Cherney Runs for Congress”, staff report, Earth First! Journal, Mabon / May 1, 1988.

[15] “Anti-Maxxam Activists Enter Political Races”, Earth News, Mendocino Commentary, March 31, 1988.

[16] Cherney and King, December 1987, op. cit.

[17] Interview with Greg King, March 31, 2010.

[18] Cherney, March 1988, op. cit.

[19] Where’s Bosco, by Darryl Cherney, 1988, featured on the Darryl Cherney music album They Sure Don’t Make Hippies Like They Used To, 1988.

[20] “Gambill Runs for Congress in 1st District”, North Coast News, March 17, 1988; and “Two More Contenders, Lionel Gambill”, press release, Country Activist, April 1988.

[21] “Darryl Cherney: a Conversation with a Remarkable Candidate”, by Michael Koepf, Anderson Valley Advertiser, (in two parts) April 27 and May 4, 1988.

[22] Koepf, April 27 and May 4, 1988, op. cit. This song was, of course, set to the tune of I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night.

[23] “Population and AIDS”, by Miss Ann Thropy, Earth First! Journal, Beltane / May 1, 1987.

[24] Manes, Christopher, Green Rage: Radical Environmentalism and the Unmaking of Civilization, Boston, MA, Little Brown, 1990.

[25] Cherney, March 1988, op. cit.

[26] “Ecofascism Comes Out of the Closet”, by Nancy Barth, North Coast News, January 21, 1988.

[27] “Darryl Cherney Responds to Nancy Barth”, by Darryl Cherney, North Coast News, February 4, 1988.

[28] Cherney and King, December 1987, op. cit.

[29] Cherney and King, December 1987, op. cit.

[30] Cherney and King, December 1987, op. cit.

[31] “Millworker Challenges Incumbent”, by John Maurer, Country Activist, March 1988.

[32] “Anti-Maxxam Activists Enter Political Races”, Earth News, Mendocino Commentary, March 31, 1988.

[33] “Hess Withdraws, Don Nelson Enters 4th District Supes Race”, North Coast News, January 21, 1988.

[34] Earth News, March 31, 1988, op. cit.

[35] “Worker Rep Candidate”, by Don Nelson, Country Activist, February 1988.

[36] See, for example, “Woodworkers Angry” by Don Nelson and “Let’s Work Together” by Cecilia Gregori, Country Activist, Oct. 1986; “Union Angry at G-P Land Swap”, North Coast News, March 5, 1987; “Union Upset With Sinkyone Exchange”, by Richard Johnson, Mendocino Country, March 15, 1987; and “Union Demands Info on G-P Land Swap,” North Coast News, March 19, 1987.

[37] “Coastal Waves: an Occasional Column”, by Ron Guenther, Mendocino Commentary, June 2, 1988.

[38] “Pritchard, Maurer Face off Tuesday in Second District Race”, by John Soukup, Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance, June 3, 1988.

[39] “Harry Pritchard Deserves 4th Term”, editorial, Eureka Times-Standard, June 5, 1988.

[40] Soukup, June 3, 1988, op. cit.

[41] “John Maurer’s Candidate Statement for Humboldt County Supervisor”, by John Maurer, Country Activist, May 1988.

[42] “A Tale of Two Candidates”, letter to the editor by Timothy Carter, Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance, May 10, 1988.

[43] “Millworker Challenges Incumbent”, by John Maurer, Country Activist, March 1988.

[44] Maurer, May 1988, op. cit.

[45] Soukup, June 3, 1988, op. cit.

[46] “IWA Local Supports Tougher Timber Cutting Regulations”, press release, North Coast News, July 1, 1987.

[47] “Why I Support the Forest Practice Ordinance”, letter to the editor by Don Nelson, Mendocino Commentary, March 3, 1988.

[48] Earth News, March 31, 1988, op. cit.

[49] “Local IWA Considers Forestry Legislation”, press release, Mendocino Commentary, March 3, 1988.

[50] “Coastal Waves: an Occasional Column”, by Ron Guenther, Mendocino Commentary, May 12, 1988.

[51] “Don Nelson: Candidate for Supervisor, 4th District”, interview by Beth Bosk, New Settler Interview, issue #31, May 1988.

[52] “Worker Rep Candidate”, by Don Nelson, Country Activist, February 1988.

[53] “IWA Rank-and-File Union Millworkers Reply: Victims of G-P’s Fort Bragg Mill PCP Spill Speak Out”, by Ron Atkinson, et. al., Anderson Valley Advertiser, December 13, 1989; Mendocino Commentary, December 14, 1989; and Industrial Worker, January 1990.

[54] “Don Nelson’s Speech at the Jesse Jackson Rally”, reprinted in the Mendocino Commentary, March 31, 1988; Jesse Jackson’s speech itself was published in the Country Activist in the April 1988 issue.

[55] “Here and There in Mendocino County”, by Bruce Anderson, Anderson Valley Advertiser, May 25, 1988.

[56] Bosk, May 1988, op. cit.

[57] “Dad for Supervisor”, by Crawdad Nelson, New Settler Interview, issue #31, May 1988.

[58] “Afterwords”, by Beth Bosk, New Settler Interview, issue #31, May 1988; Bosk also endorsed John Maurer.

[59] “Working for Wages”, by Roanne Withers, Mendocino Commentary, July 2, 1988.

[60] “Afterwords”, by Beth Bosk, New Settler Interview, issue #31, May 1988; and “Coastal Waves: an Occasional Column”, by Ron Guenther, Mendocino Commentary, May 12, 1988.

[61] “Lisa Henry on her 22nd Birthday”, Interview by Beth Bosk, New Settler Interview, January 1991.

[62] “IWA Reaffirms Support for Measure B”, press release, Anderson Valley Advertiser, May 25, 1988.

[63] “Put Up or Shut Up”, letter to the editor by Don Nelson, Anderson Valley Advertiser, May 25, 1988.

[64] Cherney and King, December 1987, op. cit.

[65] “Earth First! Activist Joins New York Protest,” by Marie Gravelle, Eureka Times-Standard, January 14, 1988.

[66] “Earth First! Proposes Redwood Wilderness”, North Coast Earth First! press release, Earth First! Journal, Eostar / March 20, 1988.

[67] “Fish & Game Axes Clearcuts”, EcoNews, January 1988.

[68] “A Bad Proposal for Humboldt”, editorial, Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance, May 10, 1988.

[69] “Timber Outlook”, by Bob Martel, Country Activist, June 1988.

[70] “A Bad Proposal for Humboldt”, editorial, Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance, May 10, 1988.

[71] “Triple Victory in ‘Three Day Revolution’”, by Darryl Cherney, Earth First! Journal, Dec. 21 (Yule), 1988 (also published in the Anderson Valley Advertiser; and in the Country Activist under the alternate title “The Cahto Story” in the Feb. 1989 and March 1989 issues.

[72] “Humboldt Voters Focus on Prop 70”, by Marialyce Pedersen, Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance, June 3, 1988.

[73] Pedersen, June 3, 1988, op. cit.

[74] Pedersen, June 3, 1988, op. cit.

[75] “The Real Issue Here is Jobs”, paid advertisement, various publications, including Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance, May 24, 1988.

[76] Pedersen, June 3, 1988, op. cit.

[77] “Guerilla Tree Planters Invade Maxxam Clearcut”, press release, Mendocino Commentary, March 17, 1988.

[78] “Guerillas Plant Redwoods”, by Berberis Nervose, Earth First! Journal, Beltane / May 1, 1988.

[79] “Pacific Lumber Files Suit to Keep Protesters Off its Land”, by Mark Rathjen, Eureka Times-Standard, April 8, 1988.

[80] Nervose, May 1, 1988, op. cit.

[81] Rathjen, April 8, 1988, op. cit.

[82] “Darryl Cherney Runs for Congress”, staff report, Earth First! Journal, Mabon / May 1, 1988.

[83] Rathjen, April 8, 1988, op. cit.

[84] Harris, David, The Last Stand: The War between Wall Street and Main Street over California’s Ancient Redwoods, New York, NY, Random House, 1995, Pages 227-29.

[85] Harris, op. cit.

[86] Harris, op. cit.

[87] Nervose, May 1, 1988, op. cit.

[88] “20 Arrested in Kneeland Anti-Logging Protest”, Eureka Times-Standard, April 14, 1988.

[89] Nervose, May 1, 1988, op. cit.

[90] “20 Arrested in Kneeland Anti-Logging Protest”, Eureka Times-Standard, April 14, 1988.

[91] Nervose, May 1, 1988, op. cit.

[92] “Old-Growth Logging Suspended”, by Andy Alm, EcoNews, May 1988.

[93] “Pacific Lumber Co. Denies Money Diversion to Maxxam”, Eureka Times-Standard, April 16, 1988.

[94] “P-L Helps Hurwitz Buy Kaisertech”, Takeback, Volume 1, #1. February 1989.

[95] “P-L Plans for Cutting Old Growth Under Fire”, by Howard Davidson, Eureka Times-Standard, April 22, 1988.

[96] “Old-Growth Logging Suspended”, by Andy Alm, EcoNews, May 1988.

[97] “New Battles in the Maxxam Campaign”, by Greg King and Berberis Nervose, Earth First! Journal, Litha / June 21, 1988.

- Log in to post comments