Chapter 24 : El Pio

By Steve Ongerth - From the book, Redwood Uprising: Book 1

Download a free PDF version of this chapter.

“The anti-corporate sentiment voiced by the very people who labor in the woods and mills could be a powerful force in the struggle to save forests and local timber jobs. However, the workers lack a militant organization with a coherent strategy for achieving that goal. In that vacuum, a worker-environmentalist alliance has a chance to develop.”

—Don Lipmanson.[1]

“This is the Pearl Harbor to our North Coast, and we’re going to mobilize people. We look forward to mill workers joining us on the line when they realize our interests are theirs.”

—Judi Bari[2]

While the controversy over the spotted owl, The Lorax, and Forests Forever continued to escalate, at long last, LP’s actual reason for the closures of the Potter Valley and Red Bluff mills came to light. The mill had closed in April and there were hopes and rumors that the mill would be sold to another operator and reopened, but it was not to be.[3] No sooner had L-P been fined by the California State water quality agency to clean up contamination of the Russian River caused by its Ukiah mill[4], when the Los Angeles Times broke to story that the company was in the final stages of negotiating an agreement with the government of Mexico to open up a secondary lumber processing facility at El Sauzal, a small fishing village near Ensenada in Baja California.[5] This new 70-100 acre mill would serve as a drying and planing facility that would process raw logs shipped out of California and elsewhere. However, it was also evident that the Mexican Government had jumped the gun in revealing the details of the proposal before L-P had crafted their P.R. strategy.[6] Caught red handed, L-P reluctantly admitted what timber workers and environmental activists had suspected might be true for several months, that the company was engaged in cut-‘n-run logging.

According to the article, the company’s application was part of the growing move by multinational corporations to take advantage of the maquiladora program—a forerunner to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—which was designed to allow them to take advantage of favorable, liberalized investment laws there. Likewise, corporations would also benefit from much laxer environmental regulations and substantially cheaper wages, averaging approximately $0.50 per hour, for example for mill workers, as opposed to $7-$10 per hour in nonunion facilities in California. L-P had planned to export as much as 300 million board feet of unprocessed “green” lumber for processing in Mexico, where they would employ 1,000. Had those jobs stayed in California, they would have kept the laid off millworkers employed.[7]

Environmentalists, who had been complaining about L-P’s exporting jobs, overcutting, and destroying the resource base for years, were angry, but hardly surprised. It made no sense whatsoever to them to locate a redwood processing facility anywhere but within the area in which redwoods still grew, and they immediately accused L-P of ulterior motives.[8] Betty Ball elaborated:

“(L-P’s move is a) blatant attempt to avoid our own environmental regulations, and instead go to Mexico where they won’t have to worry about a regional water quality board which is threatening to fine them $300,000 in a lawsuit like the one filed over toxic emissions from their pulpwood plant in Samoa.”[9]

Tim McKay of the North Coast Environmental Center accused L-P of yet another divide-and-conquer tactic, declaring:

“It’s ironic that the same company that has done so much to distribute yellow Styrofoam balls and ribbons as a symbol of the plight of the lumber workers, and to pit them against the conservationists…is secretly negotiating to export jobs. It is clear that the yellow ribbons are more truly symbolic of the fact that timber workers are hostages to a ruthless industry.”[10]

Gail Lucas decried the questionable economics of the proposal, saying, “Those jobs in Mexico could be jobs for Northern California. People just don’t seem to understand that last year alone, log exports from the Pacific Nortwest meant the exporting of 37,000 potential jobs.”[11]

L-P had evidently been counting on the unions, gyppos, and politicians to help them once again shift the blame to “unwashed-out-of-town-jobless-hippies-on-drugs”, but the company had used this trick far too many times to be taken seriously. Richard Khamsi, business agent for the Humboldt-Del Norte County Central Labor Council of the AFL-CIO called L-P’s move “socially irresponsible”, and further declared, “Those [soon the be lost] manufacturing jobs are extremely important to this area.” Gary Haberman denounced the company’s plan as “un-American” and pointed out that local workers would be at a competitive disadvantage due to the working conditions extant at the Mexican location, which he described as “slave-like”. Doug Dickson, official for the statewide social workers union agreed that the move “(Would) impoverish the working community.” Mike Evers of the Humboldt County Public Employees Association agreed, opining that in Baja California, L-P, “(wouldn’t) have to agree to eight-hour days, (and) industrial actions (wouldn’t) be a problem, (because) they (wouldn’t) have to pay workers compensation when someone loses a finger.”[12]

In Mendocino County, even IWA Local 3-469 representative Don Nelson lashed out at Louisiana-Pacific in a letter to Doug Bosco, declaring:

“L-P’s blatant disregard for workers and communities of the North Coast by their proposal to move the planning and drying of their redwood lumber to Mexico demands action on your part immediately…(L-P’s) problem is corporate mismanagement that is leading to the destruction of their North Coast timber base. L-P’s overcut of the North Coast has been documented.”[13]

“These corporations are robbing the natural resources of Northern California and we’re getting less and less in return. It’s bad enough the profits go somewhere else, now the jobs are too.”[14]

The announcement shocked other locals, including Walter Smith, whose gyppo operation had performed many cuts for LP. As early as 1985, Smith had expressed frustrations with LP, albeit discretely.[15] After L-P made their intentions clear, Smith felt that the time for discretion was long past. “The real value of [timber] wages and benefits has declined over the past ten years…workers feel betrayed, and they’re mad as hell,” declared Smith.[16]

The announcement even angered politicians normally willing to kowtow to Corporate Timber.[17] For example, Assemblyman Dan Hauser was incensed that his first knowledge of the move had come from the Los Angeles Times even though he and other lawmakers had been “negotiating” with L-P (as well as G-P and Maxxam). “L-P is treating the North Coast like a third world country,” Hauser declared in a press statement, and threatened to propose legislation that would require that redwood milling operations take place within the county or local region where the wood was logged.[18] “In the long run it will export jobs and lead to potential overcutting and destruction of the resource base,” he further warned. Meanwhile, State Senator Barry Keene stated, “It really erodes their credibility for them to say that they’re benefactors in the community and then to act as predators. I think we need to begin looking at this in an adversarial framework, and I’m certainly going to begin doing that.”[19]

With few allies to call upon, L-P invoked “economics” to justify their actions. Shep Tucker hastily denied that the company was exporting jobs, that the new mill would actually facilitate the expansion of L-P, that its location—where the annual rainfall averaged less than 9 inches—was chosen due to the climate being more favorable to drying lumber, and that the plant would better serve its customers in Southern California and the American Southwest.[20] Tucker also denied that there would be an increase in the rate of redwood logging on the north coast.[21] When pressed, however, he conceded, “Look, it’s a global economy, and it’s no secret we’re going to make savings in labor costs. We want to build where we can get good quality and make a profit, which is what (business is) all about. I’m not afraid to say that.”[22]

The Santa Rosa Press Democrat didn’t find Tucker’s arguments at all convincing, opining:

“The truth is that L-P wants to build a mill in Ensenada, 90 miles south of San Diego, because labor is cheap there—much cheaper than in Mendocino County, and lower costs mean lower prices and larger profits, both reasonable and important goals for a business, but businesses must do more than cut costs. They must be good citizens in the places where they do business.

“In that area, Louisiana-Pacific is stumbling. It’s southern strategy has managed to offend almost everybody in Mendocino County—from environmentalists who fear a wholesale attack on forests to timber industry workers who see their jobs sailing away.”[23]

Only the Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance editor Glenn Simmons, who was always willing to follow Corporate Timber—even off the edge of a cliff if asked—seemed willing to swallow Tucker’s explanation, opining:

“The decision by Louisiana-Pacific to locate a redwood remanufacturing plant in Mexico is one based on economics. Because the L.A. Times broke the story, with the Times-Standard running a similar story shortly thereafter, an alliance of politicians, union leaders, and environmentalists gathered together to hold a news conference blasting L-P’s plans last week.

“Did they listen to L-P spokesman Shep Tucker? No. They simply ignored L-P’s assertion that by locating the plant in Mexico, the company will become more competitive and stronger in a growing international market. Tucker insists that the Mexico based plant will help maintain existing North Coast jobs.

“Union leaders such as Gary Haberman, Mike Evers, and Dough Dickson, environmentalist Tim McKay, Assembly man Dan Hauser and state Sen. Barry Keene all resorted to knee jerk reactions to unfairly blast L-P…”[24]

Perhaps one might have wanted to Simmons if he believed that absolutely everything Tucker said was the truth and if so, on what basis did he stake his claims? L-P’s alleged talk of expansion was curious given the fact that only ten months earlier they had decried the lack of logs available to keep the aforementioned mills open, “due to environmental lawsuits”—lawsuits which didn’t actually exist. Despite LP’s closing those facilities, plus a mill in Chico and partial cutbacks in Cloverdale, the company had announced record semi-annual earnings, equaling $88.3 million—a 31% increase—in addition to record sales totaling $993.1 million for 1989. The company was, at that time, the world’s second largest lumber producer, operating 115 plants employing 14,000 in the United States and Canada. [25] L-P had grown “like a cancer”, while timber prices had grown rapidly and pulp prices had exploded in the previous two years. L-P couldn’t very well claim poverty.[26]

Mendocino County was certainly up in arms. The manner in which news about the move had been broken was the main topic of concern at the Board of Supervisors meeting on September 19, 1990. Norm de Vall was especially angry and went as far as to suggest that consumers, labor unions, and environmentalists should unite and call a consumer boycott (as they had four years previously to oppose Garlon spraying). “Thousands of jobs, thousands of homes are going offshore. Those built here will be very expensive because of that,” he declared. Liz Henry shared similar sentiments, and the two were unexpectedly joined by James Eddie, who was not normally one to rock the boat. He accused L-P of, “Moving us back to a colonial state (and that similar corporate moves were) moving us toward a society of either the very rich…or the very poor (leading to) the erosion of the working middle class.” Meca Wawona, a long time environmental activist (one of four present that spoke out against the move) declared that L-P’s claims that no jobs would be lost was untenable, because the decision would enable further automation and replacement of mixed use forestry with tree plantations, automation, and waferboard.[27] The supervisors placed an item on the agenda for their October 10, 1989 meeting on the issue and invited L-P to send a representative to explain their reasoning for the move.[28]

L-P had not been present but indicated that representatives would be available by October 10 to offer their perspective on the matter. Shep Tucker indicated that they had elected not to attend the September 19 meeting, because they “chose not to get into a hissing match” with the supervisors. He also warned them that neither they nor the state legislature could “dictate free enterprise” He further declared, “(The supervisors are) going to have to realize we didn’t have an option in the matter…(the Los Angeles Times article) was not our choice.” He then reiterated that L-P was “wholly, 100 percent committed to Northern California,” and again proceeded to shift the blame for the company’s move to the environmentalists.[29]

Then, displaying even greater chutzpah, L-P officials showed up unannounced at the September 25 supervisors meeting, avoiding any contact with the angry citizens prepared to confront them two weeks later. The company’s sleight of hand had been enabled by supervisor Marilyn Butcher who allowed L-P’s western division manager Joe Wheeler—one of the three company officials present—to read a prepared statement explaining its reasons for the move, and further declare:

“I was terribly disappointed with the reaction (of the supervisors) without even giving us a call…I am sure the suggestion of a boycott of L-P products called for by Supervisor de Vall was premature, and reviewing the project as I have outlined, will not only be advisable, since the only people hurt by a boycott would be the employees of Louisiana-Pacific.”

Marilyn Butcher and Nelson Redding responded approvingly to this and other statements by L-P spokesmen Wheeler, Tucker, and Chris Rowney, but the other supervisors were angered. Liz Henry stated that while the new mill might not result in the loss of jobs, it was not adding any new ones. Jim Eddie was even angrier than he had been at the previous meeting, pounding his fist on the desk, stating scoldingly that the county could no longer trust L-P given their closures of the Potter Valley and Red Bluff mills—even though more L-P logging trucks could be seen hauling timber than ever before. He then accused the corporation of being un-American, and more akin to being an outsider than the environmentalists the latter so quickly blamed for the county’s economic ills, stating, You may have run the (Potter Valley) mill for a while, but I have lived all my life with it.” Norm de Vall subsequently accused L-P of playing politics by showing up announced before the meeting where the discussion over the move had been scheduled. This statement drew a strong rebuke from Butcher, who retorted, “Norman you boggle the mind,” and accused him of leaving the initial meeting early to inform environmentalists of the October 10 meeting, a charge de Vall denied.[30]

If anything the opposite was true, and in response to Butcher, de Vall was incensed and agreed to lend his support to local environmental and labor leaders who were demanding that L-P appear at the October 10th meeting to face public scrutiny. In exchange, the leaders agreed to appear at a press conference organized by de Vall the next day, September 26.[31] At the event, de Vall criticized Wheeler’s comments as being, “an embarrassment to local government in Mendocino County.”[32] IWA Local #3-469 business agent Don Nelson also rattled his saber over L-P’s planned move to Mexico, calling the announcement, “shocking.” He further stated, “It’s absolutely contrary to all of the policies of any timber company in the country and it breaks the faith of the residents of the county and the communities that depend on our own timber resources. It’s bad enough the profits go somewhere else; now the jobs are too.”[33] Walter Smith denounced L-P’s “Wall Street economics (that) maximized profits and liquidated assets (which) threatened timberlands in Northern California.”[34] Nelson and de Vall concentrated their ire on L-P’s profiteering, but said nothing about the company’s toxic emissions, its destructive clearcutting, or its exploitative treatment of its workers.

De Vall’s and Nelson’s proposed response was fairly impotent as well, suggesting little beyond lobbying elected state officials, such as Barry Keene and Doug Bosco. This was evidently too much for Judi Bari, who was present at the event.[35] She declared, “L-P had given new meaning to the ‘cut and run’ theory.” [36] She then pointed out that Keene and Bosco were part of the problem, themselves being too willing to kowtow to the whims of the corporations, succumbing to “bare corporate greed, careening over a cliff with a madman in control.” Bari then suggested (justifiably) that Nelson was little more than a figurehead for G-P management. Nelson exploded, again denouncing National Tree Sit Week, and declaring Earth First!, “so far outside (of) the mainstream (that) they’ve lost all credibility.” He then stormed out of the Supervisor’s conference room “with de Vall close at his heels.”[37] This conference, shown on local cable access community television was witnessed by many interested residents of Mendocino County, including Anna Marie Stenberg in particular.[38]

The county residents were to be disappointed if they thought L-P would actually show up and face their scrutiny, however. Shep Tucker made it quite clear that company representatives would not appear, declaring, “We have said what we needed to say. It’s not in our best interests to continue the debate.” He also admitted that their main reason for showing up two weeks previously was specifically to avoid confrontation with the environmentalists. [39] The issue remained on the agenda for the October 10 Supervisors’ meeting, however, and that allowed critics of the move to not only appear and voice their mind, but to hold a protest rally on the county courthouse steps on the main thoroughfare through Ukiah preceding the meeting as well.[40]

At the meeting itself, Supervisor de Vall opened discussion by reminding everyone that the board had not yet taken a position on the issue. He introduced a draft of a letter for board approval to be addressed to California Senators Allan Cranston and Pete Wilson as well as California Governor Deukmejian, with copies to be sent to Bosco, Keene, and Hauser. The letter addressed L-P’s move and the threat that caused to local timber jobs, the potential for the loss of jobs and local timber related operations to jeopardize the Eureka Southern Railway, and preserving the timber industry (as opposed to the pulp industry), and the potential banning of log exports. Supervisor Nelson Redding, consistently a voice for corporate timber was noticeably absent. [41] Supervisor James Eddie focused on the effect changing L-P industrial focus would have on county tax revenue. Recently elected Supervisor Liz Henry, in her first year of service, proved herself to be a stark contrast to her predecessor, and she stated that the conflict was really about ethics and treating people with dignity, including the County, the workers, and the Mexican people.[42]

When the public comment period commenced, it became readily apparent why Wheeler had elected to appear two weeks previously. During the public comment period, speaker after speaker denounced the corporation’s proposed move.[43]

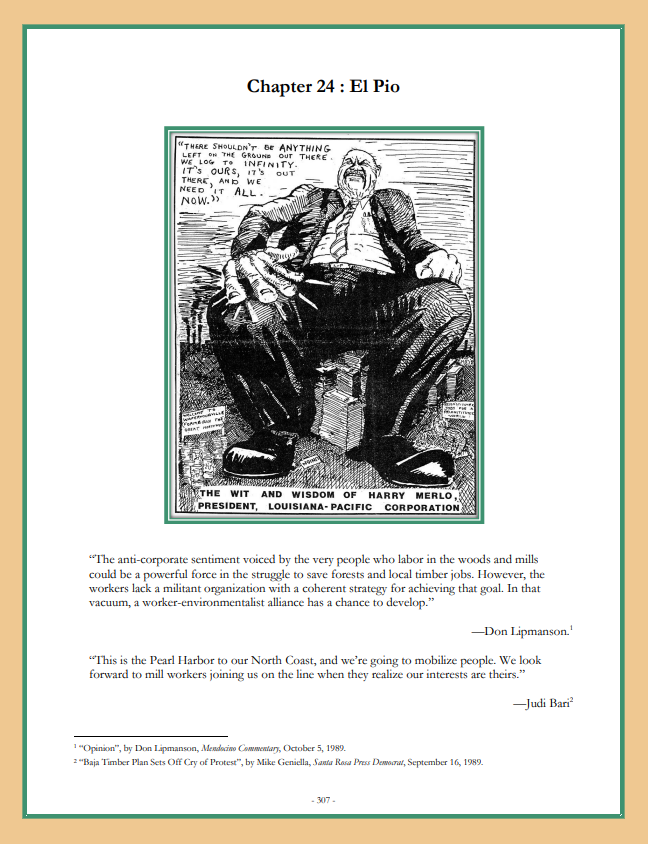

Bill Johnson decried the “loss of local control and the loss of resource base,” and he denounced Merlo’s “logging to infinity” brand of forestry.[44]

Larry Sheehy, representing the Mendocino Environmental Center (MEC), cited precedent involving closing steel mills in Pennsylvania in 1986, suggesting that the board could exercise the power of eminent domain to seize L-P’s holdings locally.[45]

Herb Blood excoriated L-P for pollution the Russian River.[46]

Local timber operator Bill Mannix scoffed at L-P’s professed reason for its establishment of a plant in Mexico, namely the climactic advantages for drying boards by pointing out that San Diego offers the same climate. Mannix instead submitted that the company’s real motivation was cheap labor.[47]

Naomi Wagner, an environmental activist who was concurrently involved in a David-versus-Goliath struggle by her Sherwood Road Protective Association (SherPA) against L-P for unpaid road assessments, stated that it was quite clear that the corporation was not negotiating in good faith. She argued that L-P had been blocking all attempts by the County appointed Mendocino County Forest Advisory Committee to gather key figures upon which to base a realistic inventory of the company’s resources.[48]

Class issues were a major focus of the discussion as well. Willits resident Jack Reynolds elaborated on the matter of labor conditions, noting that L-P could save as much as $30,000 annually per worker by relocating to Mexico, where the average hourly wage was $0.88. He cited examples of 700 businesses, like L-P, who had followed suit already.[49] He further went on to state that L-P’s actions were not “un-American” as many critics had previously claimed, suggesting instead that the corporation was “as American as apple pie and motherhood” when it came to capitalism. He then referred to the long and bloody history of employing class exploitation of workers, particularly Chinese laborers at the turn of the 20th Century. He described the working conditions in Ensenada, Mexico as “abysmal” and the shantytowns in which the workers lived as “sinkholes.” “The enemy of job security is greed,” he said, “not spotted owls or tree sitters.”[50]

Ludie Cardwell, who claimed to own 220 acres of forest with 700 trees ready to be cut, was the only speaker to support L-P’s planned move, and insisted that the rest of the speakers were nothing more than “socialists and communists,” and that they would not scare him off. Like so many other apologists for corporate plunder, Cardwell argued that he didn’t blame the corporation for its attempt at capital flight, citing local hostility as a justifiable excuse for such actions, and denounced the banning of exports as “un-American.” Supervisor de Vall responded by explaining that the United States banned the exports of many resources, adding that if the issue were one of National Security, and redwood products were deemed necessary for military purposes, their exports would have already been banned.[51]

Judi Bari offered a stark contrast to Cardwell. She accused L-P of holding Mendocino County hostage and offered her support for the eminent domain idea. She also stated that L-P treated its workers as badly as it did the forests, which brought an angry response from Supervisor Marilyn Butcher, the board’s most outspoken Corporate Timber apologist. Butcher parroted the (by now hackneyed) argument that Earth First! was anti-worker, and cited the Cloverdale tree spiking incident as proof. Bari attempted to respond, but was interrupted repeatedly by Butcher, the latter evidently convinced that she had scored a rhetorical victory, but also apparently unwilling to face a potential challenge from Bari. “Let her speak!” shouted many voices from the audience, until Butcher became silent. Bari responded by reminding everyone that Earth First! had not spiked the tree that had injured Alexander, and that the fault lay with L-P, because of their lax safety standards, and that the company had knowingly sent the log through the mill, even though it knew it had been spiked. She also noted that not all Earth First!ers—herself included—endorsed tree spiking.[52]

If Bari’s retort had taken the wind out of Butcher’s sails, she was soon to be outdone by her partner, Darryl Cherney, who—outfitted in a Mexican serape and sombrero—was tuning his guitar, and announced that he was about to offer a somewhat differently styled testimony, “to stimulate the crowd’s ‘right-brain’ activity.”[53] Butcher looked noticeably perturbed as Cherney began singing the following song:

He came from the clearcut hills of Roma,

To rape the redwoods of Sonoma,

He could clearcut forest like no other,

He said he learned his from his butcher and his mother.El-l-l-l Pio…

What have you done to MendocinoNow El Pio took his orders straight from the divinity,

Who said to him, “El Pio, thou shalt log to infinity!”

Then El Pio gets this great idea and he says, “AHA!”

I’ll move my entire milling operation down to Ba-JA!!!!El-l-l-l Pio…

What have you done to MendocinoThen one day he gets a phone call from his brother, G-Pio,

Who says to him, “I think I’m down to my last tree-o,”

But El-Pio says to him, “No problem, just scrape-a’ the forest floor!

Grind it up, glue it back to together, make-a’ wafer board!”El-l-l-l Pio…

What have you done to MendocinoThen one day he gets news that causes him a-great pain,

When the Supervisors showed some courage and declared eminent domain!

And reality hits him like some bad dream-a,

When he finds a note that says, “No compromise, Tierra Prima!”El-l-l-l Pio…

What have you done to Mendocino [54]

The mostly partisan audience loved it, and many joined in on the last chorus, which brought the house down. Supervisors de Vall and Henry even smiled, though Butcher and Eddie were visibly exasperated. The board ultimately voted to send the letter suggested by de Vall by a vote of 3-1, with Butcher the only dissenting voice.[55]

The reaction in Humboldt County only slightly less dramatic. A week after the Mendocino County supervisors’ meeting, at the Humboldt County Board of Supervisor’s meeting on October 18, 1990, Cherney, similarly dressed, repeated his performance of El-Pio. He also asked why the company simply didn’t open the new facility in the old mill in Potter Valley. The Humboldt County Board of Supervisors were somewhat more responsive, voting 5-0 (Sparks and Pritchard included) to send a letter to L-P admonishing the corporation to drop their plans for their Mexican expansion. The letter read, in part:

“Humboldt County workers could and would occupy the jobs L-P intends to create in Mexico if the remanufacturing plant were sited here instead. We entreat you to bear in mind Humboldt’s first-rate workforce and the willingness of local leaders to work with you to create a feasible Humboldt County option.”[56]

The normally knee-jerk reactionary Anna Sparks downplayed her willingness to challenge L-P declaring, “All the letter says is that we’d like to talk to Merlo. I would support anything that looks at keeping the jobs here,” though she added (in reference to Cherney’s serenade), “It’s better to talk than to protest.”[57] This seemed to match the attitudes of their fellow supervisors representing the county on their southern border. That same day, Mendocino County Supervisor Eddie proposed sending an equally ineffectual letter to Keene and Hauser, asking for the state officials to draft legislation to support the local timber economy.[59] And that “deal” heralded a disturbing trend.

No sooner had L-P’s Mexican adventure been revealed when the San Francisco Chronicle reported that several other timber corporations, including Georgia-Pacific, were exploring the possibility of setting up shop in Russia. When confronted with reporters G-P spokesman David Odgers would only state that the company pursued business opportunities anywhere it could find them, including the “international marketplace.” This brought a response from Darryl Cherney who declared,

“In their attempts to modernize the Soviet Union, the Russians are making a mistake in thinking that current American forestry technology is good. Maybe we’ll need to establish an Earth First! branch in the Soviet Union. (It’s kind of ironic that) when we are holding demonstrations, the counterdemonstrators tell us to ‘Go to Russia!’ Look who is going to Russia.”[60]

Within weeks, L-P broke ground for their new facility in Mexico.[61]

At this point, mere talk was cheap. The notion of eminent domain, though ignored by the Supervisors in both Humboldt and Mendocino Counties, wouldn’t go away, however. The idea horrified L-P as well as other representatives of corporate timber. Shep Tucker described the idea as “scary”, while Bill Dennison, president of the Timber Association of California stated, “Every property owner should be shaking in their shoes at the idea…it sounds like 1930s Germany to me.” Betty Ball, on the other hand, suggested the idea was entirely within the realm of American history, even if it was not currently popular. She declared:

“Politicians aren’t touching it with a 10-foot-pole…They’re not even going to openly discuss it. They will if they see a grassroots groundswell, but not until then… (however) I’ve seen a dramatic change in the past six months, with the escalation in logging, the mill closures, Harry Merlo’s comment that he wants it all and he’ll take it all, (Louisiana-Pacific’s) plans to build a plant in Mexico…

“People are really changing their ideas about private property rights. With a right goes a responsibility and the corporations are being totally irresponsible…They may own the land, but on that land are streams, creeks and wildlife that are part of the public trust, not their personal property.”[62]

Ball’s taking of the local community’s political pulse was not unrealistic. Corporate Timber’s manufactured consent was slipping away minute-by-minute.

[1] “Opinion”, by Don Lipmanson, Mendocino Commentary, October 5, 1989.

[2] “Baja Timber Plan Sets Off Cry of Protest”, by Mike Geniella, Santa Rosa Press Democrat, September 16, 1989.

[3] “PV Mill Closure; Sawmill Expected to Run Out of Logs Later This Week”, by Keith Michaud, Ukiah Daily Journal, April 24, 1989.

[4] “State Fines L-P $10,000; Holds $300,000 Hammer Over Local Lumber Company’s Head”, by Keith Michaud, Ukiah Daily Journal, August 25, 1989.

[5] “L-P Negotiating Deal for Baja; Lumber Producer to Build Plant”, by Chris Kraul, Los Angeles Times, reprinted in the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, September 15, 1989.

[6] “LP Plans Mexico Expansion”, by Richard Johnson, Mendocino Country Environmentalist, September 15, 1989.

[7] “Jobs Automation and Exports”, by Eric Swanson, Mendocino Country Environmentalist, July 22, 1992.

[8] “Mexico Lumber Remanufacturing Raises Furor”, staff report, Willits News, September 20, 1989.

[9] “Baja Timber Plan Sets Off Cry of Protest”, by Mike Geniella, Santa Rosa Press Democrat, September 16, 1989.

[10] “L-P Exports Jobs to Baja”, by Tim McKay, EcoNews, October 1989.

[11] Geniella, September 16, 1989, op. cit.

[12] “Local Officials Condemn L-P Move”, by Marie Gravelle, Eureka Times-Standard, September 26, 1989.

[13] “L-P Plan Under Attack Again”, by Keith Michaud, Ukiah Daily News, September 27, 1989. Emphasis added.

[14] Geniella, September 16, 1989, op. cit.

[15] “Kenneth O. Smith and Walter Smith: Gyppo Partners, Pacific Coast Timber Harvesting”, Interviewed by Beth Bosk, New Settler Interview, Issue #21, June 1987.

[16] Lipmanson, October 5, 1989, op. cit.

[17] “Local Officials Condemn L-P Move”, by Marie Gravelle, Eureka Times-Standard, September 26, 1989.

[18] “Mexico Lumber Remanufacturing Raises Furor”, staff report, Willits News, September 20, 1989.

[19] Gravelle, September 26, 1989, op. cit.

[20] Johnson, September 15, 1989, op. cit.

[21] “Mexico Lumber Remanufacturing Raises Furor”, staff report, Willits News, September 20, 1989.

[22] Geniella, September 16, 1989, op. cit.

[23] “L-P Finds a Short Cut to Orange County”, editorial, Santa Rosa Press Democrat, September 16, 1989.

[24] “Over the Edge: Business Decision Dictates Location”, editorial by Glenn Simmons, Humboldt beacon and Fortuna Advance, September 28, 1989.

[25] Johnson, September 15, 1989, op. cit.

[26] Lipmanson, October 5, 1989, op. cit.

[27] “Proposed L-P Mexico Plant Angers Supervisors”, by Keith Michaud, Ukiah Daily Journal, September 20, 1989.

[28] “L-P Roasted in Abstentia: the Opposition Makes its Case”, by Rob Anderson, Anderson Valley Advertiser, October 11, 1989.

[29] Michaud, September 20, 1989, op. cit.

[30] “Tempers Flare in L-P Mexico Deal”, by Keith Michaud, Ukiah Daily Journal, September 26, 1989.

[31] Lipmanson, October 5, 1989, op. cit.

[32] “L-P Plan Under Attack Again”, by Keith Michaud, Ukiah Daily News, September 27, 1989.

[33] “Mexico Lumber Remanufacturing Raises Furor”, staff report, Willits News, September 20, 1989.

[34] Michaud, September 27, 1989, op. cit.

[35] Lipmanson, October 5, 1989, op. cit.

[36] “Mexico Lumber Remanufacturing Raises Furor”, staff report, Willits News, September 20, 1989.

[37] Lipmanson, October 5, 1989, op. cit.

[38] Interview with Anna Marie Stenberg, held October 18, 2009.

[39] “L-P-Mexico Protesters Set to Rally”, by Lois O’Rourke, Ukiah Daily Journal, October 9, 1989.

[40] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[41] “County Seeks State, Federal Help to Prohibit Raw-Lumber Exports”, by Mike Beeson, North Coast News, October 19, 1989.

[42] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[43] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[44] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[45] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[46] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[47] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[48] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[49] Beeson, October 19, 1989, op. cit.

[50] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[51] Beeson, October 19, 1989, op. cit.

[52] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[53] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[54] El Pio, lyrics by Darryl Cherney, music by Darryl Cherney and George Shook, from the album Timber, 1991; Cherney actually wrote this song for Judi Bari’s two daughters. The last verse was later altered, and the first two lines were changed to: “Then one day he gets news that causes him great concern-o / When he finds out that both of his feller bunchers have been sterno-ed.” The reasons for this change are described several chapters later.

[55] Rob Anderson, October 11, 1989, op. cit.

[56] “Board Urges L-P to Drop Mexico Plan”, by Marie Gravelle, Eureka Times-Standard, October 19, 1989.

[57] Gravelle, October 19, 1989, op. cit.

[58] Beeson, October 19, 1989, op. cit.

[59] Gravelle, October 19, 1989, op. cit.

[60] “Article Says G-P is Going to USSR”, by Lois O’Rourke, Ukiah Daily Journal, October 22, 1989. Emphasis added.

[61] L-P Breaks Ground In Mexico; Critics Lash Out”, UPI Wire, Eureka Times-Standard, November 8, 1989; and “L-P Says Mexico Plant Won’t Coast North Coast Jobs”, by Charles Winkler, Eureka Times-Standard, December 19, 1989.

[62] “Attempts to Retake Forest Under Way”, by Judy Nichols, North Coast News, October 19, 1989. Dennison didn’t think too highly of preservationists or environmentalism, as he was an ardent Christian Fundamentalist, and had, in June of 1988 issued a document, written by fellow Fundamentalist H. L. Richardson, declaring holy war on the “heathen left.” (see “Timber's Holy War”, by Darryl Cherney, Country Activist, August 1988 for details).

- Log in to post comments