Chapter 21 : You Fucking Commie Hippies!

By Steve Ongerth - From the book, Redwood Uprising: Book 1

Download a free PDF version of this chapter.

“Fort Bragg has bred a race of people who live in two-week stints, called ‘halves’ which end every other Thursday with a trip to the bowling alley for highballs and to cash the paycheck. The most altruistic among these are church-going, family-and-roses, four-holidays-a-year American workers. At the other end of the line (sometimes in the same body) are people who would kill hippies with a certain fundamental zest; who are still angry about events of twenty years ago and have been patiently tearing up the woods ever since…People want to work the last few years [while the forest lasts], go back into the hard-to-reach places and cut those last trees, the way a tobacco addict wants to smoke all the butts in the house when stranded.”

—Crawdad Nelson, June 28, 1989

“It’s time for loggers—and employees of nuclear power plants, for that matter—to consider the idea that their jobs are no longer honorable occupations. They have no God-given right to devastate the earth to support themselves and their families.”

—Rob Anderson, June 21, 1989

With the arrival of summer, Corporate Timber organized its biggest backlash yet against the efforts by populist resistance to their practices, particularly the possible listing of the Northern Spotted Owl as an endangered species. Masterfully they whipped up gullible loggers and timber dependent communities into a mob frenzy, framing the very complex issue as simply an opportunistic effort by unwashed-out-of-town-jobless-hippies-on-drugs to use the bird to shut down all logging everywhere forever. At the very least, they predicted (lacking any actual scientific studies to prove it) that listing the spotted owl as “endangered” would result in as much as a 33 percent reduction in timber harvesting activity throughout the region. Nothing could be further from the truth in the timber wars, of course, but that didn’t stop the logging industry from bludgeoning the press and public with this myth to the point of overkill.

A sign of the effectiveness of Corporate Timber’s propagandizing was the rapid adoption by timber workers, gyppo operators, and residents in timber dependent communities of yellow ribbons essentially symbolizing solidarity with the employers. [1] This symbol was far simpler than Bailey’s “Coat of Arms”, and such activity was encouraged, albeit subtly, by the corporations themselves, but the timber workers who had already been subjected to a constant barrage of anti-environmentalist propaganda were swayed easily. [2] One industry flyer even went so far as to say, “They do not know you, they have never met you, and the probably never will meet you; but they are your enemies nonetheless.” Yellow ribbons had been used for this purpose for several years already, but never on such a widespread scale. [3] Many of those sporting yellow ribbons, particularly on their car or truck antennae adopted other symbols as well. [4] These included t-shirts, bumper stickers, and signs with slogans such as “save a logger, eat an owl”, “spotted owl: tastes like chicken”, or “I like spotted owls: fried.” [5] Gyppo operators even began organizing “spotted owl barbecues” (with Cornish game hens standing in for the owls). [6]

All of this was anger directed at the environmentalists in a frenzy, which even the biggest enablers of Corporate Timber privately conceded was “knee jerk”. Pacific Lumber president John Campbell did what he could do sow more divisions by denouncing those that sought to preserve the spotted owl as “Citizens Against Virtually Everything” (CAVE). [7] Louisiana Pacific spokesman Shep Tucker declared, “We want to send a message across the country that this is not acceptable, and we can do it by pulling out all of the stops and descending on Redding in force.” [8] As if this weren’t enough, local governments of timber dependent communities, including Redding, Eureka, and Fortuna, got into the act and passed resolutions opposing the listing of the owl as endangered. [9] The climate of fear generated by this effort was so intense that Oregon Earth First!er, Karen Wood, who—with a handful of other local Earth First!ers—had walked picket lines in solidarity with striking Roseburg Forest Products workers, commented that one could not venture into a single business without seeing pro-Corporate Timber propaganda in her timber dependent community. [10]

Congressman Doug Bosco, ever eager to seize the opportunity to insert himself in the middle of a timber-related controversy, often to the consternation of the environmentalists who saw his actions as thinly veiled attempts to pander to Corporate Timber, was no exception. In early July, the Congressman journeyed to Humboldt and Mendocino Counties to express his “grave concern” for the potential economic devastation to these timber dependent economies. On Friday, July 7, Bosco met with 30 North Coast representatives of the timber industry. Later that evening he convened a press conference at the Eureka Inn. There, he declared:

“We have before us an enormous challenge as well as a great crises in the form of the spotted owl. I wanted to make the industry people and the community as a whole up here aware that that this is a very big crisis—the biggest one we have faced. It is greater than the Redwood National Park expansion. This area cannot sustain (a near 33 percent) loss (of timber harvesting activity).” [11]

Bosco tried to appear balanced and claimed that he was concerned about the Spotted Owl as well, stating:

“If we were to get rid of the old growth forests, the second growth would never be the same thing, and, in that sense, the spotted owl is a good thing, because it pointed to the fact that we have to pay close attention that is necessary to protect the species. The misfortune of the whole thing is that we apparently are going to do that in an abrupt manner that will not allow for the type of transition that we hoped for.”

In an effort to provide this supposed transition, Bosco called for legislative action that would delay the new rules created as a result of the listing—an unprecedented attempt at an end-run around the Endangered Species Act, which—if allowed—quite possibly could have greatly undermined it, thus demonstrating that the congressman’s attempts at “balance” were illusory.

Bosco’s statements were scarcely different than those of the Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance which likewise called for “restraint” and “dialog”:

“We support the effort of the US Fish and Wildlife Service in its attempt to determine the status of the spotted owl. It is a study that should have been conducted years ago. But we question the decision to shutdown (sic) logging on federal lands. The owl has not been determined to be a threatened species. What happens to the thousands of timber workers and their families when mills close while the FWS studies the owl? How will the Northwest economy, which is tenuous at best, fare?...All parties must come to the table with compromise on their agendas at next month’s public hearings on the spotted owl. We need negotiations that take place in the spirit of constructive dialog. Rhetoric needs to remain at home. Needed is a settlement conducive to the well-being of wildlife and industry.” [12]

It took a great deal of chutzpah for the one publication on the North Coast which had backed Maxxam and L-P at virtually every opportunity and constantly denounced Earth First! using precisely the same rhetoric uttered by the likes of Shep Tucker and John Campbell to suddenly claim to be a moderate voice in a debate that was already significantly skewed to the far right. They scarcely meant it in any case, because in each successive issue, the intensity of their vitriol towards the environmentalists waxed heavier and heavier to the point that it was difficult to imagine any position more reactionary than their own. This was evidenced by their opining favorably about the formation of the Yellow Ribbon Coalition in Oregon (to which WECARE was aligned), specifically:

“The Yellow Ribbon Coalition was formed to protect (timber) jobs, the timber heritage, and personal property rights. That’s why you see yellow ribbons flying on the antennas of cars and trucks.

“Throughout hundreds of small towns and cities in the Northwest, yellow ribbons are displayed. They symbolize the alarm and outrage felt when confronted with the environmentalists agenda of severely scaling back or ruining the timber industry. They symbolize the solidarity of the rural working person whose livelihood is threatened…

“In this unity there is strength. In strength there is a mobilization of political power. It is this type of unity and subsequent political power preservationist groups have used to force their agenda into the public arena.” [13]

These opinions were essentially verbatim regurgitation of the Yellow Ribbon Coalition’s own propaganda, which the Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance published a as guest editorial a mere three weeks later. [14] Such rhetoric, provided one substituted “swastika” for “yellow ribbon” and “Jew” for “environmentalist” would have been quite at home in Nazi Germany in the 1930s, and this was a connection that many environmentalists quickly recognized. [15] Tim McKay had a substantially different perspective on the symbolism than Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance editor, Glenn Simmons, declaring instead:

“When people ask me what the yellow ribbons mean, I tell them they are the symbols of the industry’s campaign against the enemy: It is the flag for what it portrays as a struggle to maintain a rural life-style and support an army of honest, hard-working middle Americans.

“I have resisted the temptation to start a campaign of green ribbons, both because I am tired of the endless adversarial relationships and because, in fact, I do know people who work in the timber industry.

“I don’t want to destroy them and I empathize with their plight. Knowing that, however, doesn’t change the fact that a time for balance is long overdue. So when an NEC member said, Why not sport rainbow ribbons?” it seemed like the perfect way not to exclude people of the yellow persuasion while presenting the need for balance and equity.” [16]

If Corporate Timber’s enablers, including the Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance were really interested in “negotiations” and “dialog”, they had an extremely odd way of demonstrating it. They certainly no hesitation in publishing opinions full of bigotry and lies about environmentalists (as well as wildly inaccurate and unscientific arguments about forestry), such as those of ICARE director David Kaupanger, which included whoppers such as:

“The preservationist groups—the force behind this political decision—are made up of members who make twice the income (the workers) do. These hard working timber workers are justifiably resentful of people who have nothing better to do than put them out of work…

“History has proven that preservation in most cases harms more than it preserves. These people would stand on the sidelines and cheerfully watch our forests burn up. I can guarantee if that happens they see to it that the burned timber will rot, rather than be salvaged to build homes with, as they did and are continuing to do in the west after the 1987 fires…

“The scientific fact (sic) is that old-growth forests, because they are decaying and are not in the vigorous growing stage of their life cycles, produce much less oxygen than young, healthy forests…

“I have a videotape of the Western Public Interest Law Conference held in Eugene, Oregon in march 1988 (attended by the Sierra Club, Earth First!, and other kindred (sic) spirits) in which the preservationists admit that they themselves care about the owl only as a means to stop the cutting of old-growth timber. They say if they didn’t have the owl as a surrogate they would have to genetically produce one.” [17]

There were few environmentalists—other than an occasional dingbat letter writer to the Earth First! Journal whose opinions certainly didn’t reflect 99 percent of the rest of Earth First! or the Journal’s contributors for that matter—who actually held such views. Nor did the vast majority of environmentalists typically write similar screeds from their own perspective full of absolute lies and vile hatred, but in any case, the Humboldt Beacon and Fortuna Advance (who no doubt had equivalents throughout other regions of California as well as Oregon and Washington) never offered them a chance to rebut such vitriol. Nor did they report that several environmentalist organizations, including the Oregon Ancient Forest Alliance, had crafted plans that would preserve the owl’s old-growth habitat, allow for the harvest of as much as 1.4 bbf in 1989, and not cost a single timber job, all from the simple act of banning raw log exports. [18]

* * * * *

Earth First! had no time to let the propaganda faze them. At the 1989 Round River Rendezvous, in late June and early July, Earth First!er Jake Jagoff had already hatched the idea of a nationwide day of tree sitting with the theme “Save America’s Forest,” and the connection between deforestation and global climate change. The Earth First!ers there reached quick consensus and chose the week of August 13 to be the target date. Darryl Cherney took on the role of national spokesman, proclaiming that together, Earth First!ers would soon make tree sitting America’s “new national pastime”, and Jean Crawford volunteered to serve as the national coordinator. Tree sits were planned in over seven states, including California, where Judi Bari would be the statewide coordinator. Only an increasingly burned out Greg King registered any hesitation, but eventually joined in the efforts, and set to work gathering equipment. [19] Accompanying the tree sitters would be coordinated on-the-ground protests in solidarity with the demonstrators positioned high up in the trees. [20] This would be one of the most widespread weeks of actions ever organized by Earth First and at the same time, each action would be locally autonomous. With each action, Earth First! was improving on its technique of coordinated, decentralized actions. [21]

Jean Crawford eloquently summarized the urgency of the actions on ecological grounds, stating

Having wasted much of their corporate forest lands, big timber companies are now devouring the National Forests as well. Forests are the lungs of the planet. In order to stop the greenhouse effect, it is not enough to just save tropical rainforests, we must stop the deforestation of America.”; [22]

Karen Wood stressed the importance of not giving in to corporate pressure:

In the midst of ‘Save a Logger—Eat an Owl’ t-shirts and the nazilike Yellow Ribbon Campaign where businesses and individuals are ostracized if they don’t fly a yellow ribbon in support of the timber industry, Oregon Earth First! continues to make a strong stand for the forests with over 75 people arrested this year alone.; [23]

Darryl Cherney stressed, however, that the event was not being conducted in direct response to the timber industry backlash against the spotted owl, but rather in response to the ongoing threats to the entire forest system of which the owl was but a symptom. He explained, “This is obviously spotted owl week, (but) the timber crisis is culminating to such an extent right now, that now’s the time to do it. We want to place (job losses) where (they belong) and that’s with log exports, automation, and corporate greed.” [24] “It’s not owls versus jobs, it’s clean water versus patio decks, fresh air versus paper towels,” he added. Judi Bari agreed, but framed the issue in terms of class, clarifying, “While yuppies from L.A. and Marin are bathing in their old-growth redwood hot tubs, a national treasure is going down the drain.” [25]

Before the actions even reached a full head of steam, however, on Monday, Louisiana-Pacific was fined nearly $750,000 for contaminating the ground water at its facility in Calpella, which had been going on for years and resulted in toxic chemicals seeping into the Russian River, which is the main source of drinking water for thousands of residents in Sonoma County to the south. Additionally, L-P’s pulp mill in Samoa and its fiberboard facility in Hayward, California were also facing increasing scrutiny from a plethora of state and federal regulatory agencies for water, air, and soil contamination. [26] One day later, OSHA announced that G-P was indeed liable for willfully exposing its workers to toxic PCBs at the Fort Bragg Mill. [27] Feeling vindicated, Treva VandenBosch stated, “I know the laws are out there to protect us, and now maybe we’re finally being heard.” [28] The news was an unexpected extra shot in the arm to the week of action.

National Tree Sit Week was more successful than anyone could have imagined. Colorado Earth First!ers staged a tree sit west of Rocky Mountain National Park in the Arapaho National Forest, protesting an impending Louisiana-Pacific cut of the Bowden Gulch Sale, which threatened old growth spruce and fir at over 10,000 feet above sea level. Tree sitters Glen Ayers, Greg Kyle, and Scott Ahorn hung a huge banner from the perch reading, “THE ROAD STOPS HERE – EARTH FIRST!”.

Meanwhile, Earth First!ers in Massachusetts staged the first ever tree sit in on the East Coast on Mount Graylock, one-eighth of a mile away from the Appalachian Trail. Earth First!ers Snaggle Tooth, Tom Carney, and others spearheaded a protest of a development which threatened the New England wilderness.

Simultaneously, tree sitters Jake Jagoff, Gus, and Mary took action for Wild Rockies Earth First! in Swan Valley, Montana, displaying banners reading “SURVIVAL or STUMPS”; “LIVE WILD”; and “STOP the RAPE”.

New Mexico Earth First! made their stand at Barley Canyon. Tree sitters Steve Forest and Gary Schiffmiller perched between 25 and 60 feet in the canopy of threatened Ponderosa Pines while Earth First!ers Katherine Beuhler and Rosa Negra locked themselves to a bulldozer using kryptonite bicycle locks. They displayed a banner reading, “SAVE SW OLD GROWTH”.

In Oregon, Earth First!ers experienced their only major resistance as they were ambushed by the USFS after spending 18 hours hauling gear 1.5 miles to their targeted location in Willamette. Earth First!er Jay Bird responded by staging a tree sit outside of Oregon Senator Mark Hatfield’s office, complete with two banners, reading “NO DEAL HATFIELD – LET JUSTICE PREVAIL” and “YOU CAN’T CLEARCUT YOUR WAY TO HEAVEN”, the latter the title and chorus of one of Darryl Cherney’s best known songs; this action made national news. Meanwhile, 100 demonstrators protested at the Willamette National Forest headquarters which had already been adorned with a banner, hung by unknown demonstrators, reading, “NATIONWIDE TREE SIT, EARTH FIRST!, CLEARCUTS STINK”. To emphasize the point, the banner hangers had sprayed the area with skunk scent.

Washington Earth First!ers organized two separate tree sits. One action took place in western Washington at Goodman Ridge in the Derrington District of the Mt. Baker Snoqualmie National Park in a proposed THP between Boulder River and Glacier Creek Wilderness Area, involving three tree sitters: Tony Van Gessel, Amy Goforth, and John Deere. The other action, organized by Okanogan Highland Earth First!, took place in eastern Washington in the Colville National Forest at the Cougar-Bear THP of the Republic Ranger District in the Kettle Range, in which tree sitters Tim Coleman and Strider Vine made their stand 75 feet in the air. Their particular action received TV coverage in Washington as well as Montana. [29]

Time magazine covered the mobilization with an article (published the week of August 28, 1989) and photographs, including one of a banner reading “stumps suck!” [30] The organizers felt the article was balanced and made a good case for tightly controlled, limited cutting of old growth forests.

By far, however, the most extensive actions took place in northwestern California. There, Earth First! staged three tree sits and nine actions in total, thus making twelve tree sits in seven states overall. [31] Two of the three California tree occupations took place in Mendocino County. [32] One of these was the first all women tree sit which took place on Sherwood Road on land adjacent to a Georgia-Pacific clearcut and a nearby L-P harvest site near the town of Fort Bragg on Monday, August 14, 1989. [33] The three women in the trees included 31-year-old Pamela McMannus, a former National Parks employee-turned-recycler from San Diego, California, from whose tree platform hung a banner that read, “STUMPS SUCK!” [34] She was joined by 22-year old Alameda resident Helen Woods, who stated:

“I am sitting in the tree to make a planetary statement: Such catastrophic behavior must cease. Corporate-patriarchal America with its Rambo mentality has got to realize the repercussions of such ecoterrorism against our Mother. How much more destruction need there be before we realize the lives that are at stake are our own? Earth First!” [35]

These thoughts were echoed by her comrade, Jenny Dalton, who declared:

“Here in the northwest a mere 5 percent of these forests vital to our existence remain. How can we, the inhabitants of this earth, turn our heads as a few corporate leaders put a price on the livelihood of all species, present and future. I am sitting in this tree to take a stand against this insanity. We the women of this tree-sit represent a populace unwilling to succumb to the madness.” [36]

Gesturing towards the G-P clearcut in which the tree-sit occurred, ground coordinator Judi Bari elaborated further, stating, “This isn’t logging; this is a massacre…These are the third-growth trees here. These are the babies, about 40 years old, that they’re taking now. They’re taking every last tree they can scrape off the dying earth.” [37]

Even though the sit did not actually occur on G-P land, the company decided to make a showing of force anyway. During the late afternoon of August 14, a security detail appeared and warned the sitters and support crew that they had been using the company’s private logging road. The road was actually an unmaintained county road leading to a smaller dirt track which had once been a county stagecoach route, but G-P claimed that the road was no longer public. [38] The security team then proceeded to record the license numbers from the demonstrators’ vehicles, but since the action did not blockade an active logging site, no law enforcement appeared. Instead, G-P spokesman Don Perry informed the press, “We told them that they were on private property and that’s about it. We’re not going to try and pull anybody out of a tree. I was amazed at their ability to get all that equipment up there. It takes strength and nerve.” [39] Louisiana-Pacific also reacted nonchalantly, but firmly to the demonstration. “We haven’t been able to confirm today that (the sitters are) actually on our land [they weren’t], but if they are, it’s trespass and we will treat it as such,” declared Shep Tucker, emphasizing that the corporation intended to invoke the ever sacred right of “private property” to log with impunity. [40]

Even though the action did not target an actual logging operation, the activists still believed their actions had a direct effect. One of the support crew, Paul Owens, whose father once worked at the G-P mill declared, “I don’t think people really understand how fast the wilderness is disappearing”, stressing the urgency of the action. [41] Judi Bari noted that the clear cutting of younger trees was an attempt by Georgia-Pacific to cut and run and liquidate their holdings. She reiterated that the union workers at Georgia-Pacific were just as much victims as the forests, because “their jobs go with the trees.” G-P spokesperson Don Perry denied that the company had plans to cut and run, repeating the familiar talking point about “replanting”, specifically that they grew 2.5 million seedlings annually. Bari countered by pointing out that the company only did this because it was required by law, and that G-P’s implementation of the same was inadequate and ineffective, because the new saplings, which had evolved to grow as understory trees could not survive exposed to the sunlight in a clearcut. Perry admitted that he couldn’t predict how many seedlings would actually grow and survive to become mature trees. [42]

The tree sitters came down on Wednesday, but the platforms and gear were then “recycled” and relocated to a location near Navarro on California State Highway 128, the main route taken by tourists from Cloverdale to Fort Bragg. [43] There the platforms were raised into the redwoods on opposite sides of Flynn Creek Road [44], and tree sitters (two men this time) hung banners reading, “CLEARCUTTING IS ECOTERRORISM” and “STOP REDWOOD SLAUGHTER”. [45]

The third tree sit, led by Greg King who was accompanied by twenty supporters, took place in Humboldt County in Arcata in the trees of State Assemblyman Dan Hauser’s front yard. According to Greg King, “Hauser wouldn’t even come outside to argue.” [46] The Assemblyman, who was sitting down to lunch, did talk to the media, however and expressed concern about the tree in his yard, at least, stating, “(It’s) a very, very old black walnut tree. I just hope they don’t hurt it.” [47] He was by no means supportive of the protesters, declaring, “If you let me know what they support, I’ll oppose that.” [48]

The actions were not merely limited to the forest canopy, and were joined not just by Earth First!ers and IWW members, but many others as well. At least six different actions also took place on the ground throughout the state. On Monday, August 14, 25 demonstrators once again protested Maxxam’s takeover of Pacific Lumber at the P-L sales office in Mill Valley. On Wednesday, August 16, 100 people protested the USFS’s subservience to Corporate Timber at their office in San Francisco. Meanwhile, Earth First!ers and IWW members assembled in the remote village of Whitethorn, near Garberville. On Thursday, August 17, demonstrators protested at Maxxam’s corporate offices in Los Angeles. [49]

* * * * *

The Whitethorn action had been organized by local residents—who called upon the support of Earth First!ers and IWW members—against the careless and destructive logging practices of the Lancasters, a local gyppo family. [50] The locals had complained for weeks about the Lancasters’ less than stellar operation, including the latter’s heedlessly speeding their trucks through the area and their encroaching on land owned by local resident, Bill Vallotton, adjacent to the logging site. [51] The demonstration had been organized as a picket and road blockade, which happened, and a fourth tree sit, which didn’t, because the loggers got word it ahead of time and focused their efforts on hauling what they’d already cut previously on that day. Working until 9:30 the previous night, hauling logged hardwoods from the Lost River, a tributary of the Mattole, the Lancasters fired guns into the air every 15 minutes, as if to loudly proclaim their presence. [52] The demonstrators made it a point to block only the trucks hauling wood away from the site, while admonishing the loggers to drive more slowly along the State Park road leading to the location. The Lancasters, led by family patriarch, Doyle, were not especially enthused by their adversaries. They had already been blockaded one month previously. [53]

Whitethorn is little more than a hamlet, consisting of a small store, a post office, an auto-repair shop, and (at the time) a pay telephone. To the southwest lies the Sinkyone Wilderness and Whale Gulch community. Twenty years previously, the first “back-to-the-landers” to settle the north coast made their homes there, and at the time, “poets, pinkos, and pushers inhabited (that town) where rednecks grew pot and hippies carried guns.” [54] Being as remote as it was, about halfway between Garberville to the east and Shelter Cove on the remotest part of the “Lost Coast”, it was far away from any sort of reliable CDF or BLM oversight (such as it was). There were also rumors and even halfway reliable reports that a number of meth labs were in operation in the area, and a few of the younger Lancasters were rumored to partake in such vices. Adding to the mystique, a number of murdered corpses had even been located by the sheriff’s offices of both Humboldt and Mendocino Counties, and word was that these had been related to the dealing of speed, but no conclusive proof had ever turned up. [55]

In fact, the initial instigator of the tension that foreshadowed what was about to ensue was not connected with either side in the standoff. During the early stages of the protest, a local speed dealer, who called himself “Maniac,” drove up to the blockade and demanded to be let through. He was thought to have one of the aforementioned labs and was anxious about the sudden attention this remote corner of the North Coast was suddenly getting. He was also in possession of a pistol, and the locals were apprehensive that he might use it if not allowed access. After a time, however, he left, flipping the bird as he sped away. [56]

There was no time for either side to exhale, however, because shortly after Maniac’s departure, the scene at the blockade intensified. Doyle Lancaster’s 70-year-old brother-in-law, known as “Logger Larry” came speeding down the local dirt track in his logging truck, charged the blockade, consisting of 30 demonstrators or so, and nearly ran down Whitethorn resident Bill Matthews. [57] “Larry” later claimed that he hadn’t intentionally meant to threaten the protesters and that he “feared for his life”, but Matthews disputed this, saying, “He was definitely going for it…it was intentional.” [58] At that point, the rest of the Lancasters lost their composure and commenced shouting at the blockaders. According to Darryl Cherney, the Lancasters had been drinking all morning and shouting insults at the locals. At one point, Whitethorn resident Mary “Mem” Hill, attempted to photograph their adversaries’ rude and provocative behavior with her camera. Lancaster’s wife, self conscious that her family’s behavior had crossed the line, scuffled with Hill. [59] Mrs. Lancaster threw a punch at Judi Bari (who was nonviolent, but was not adverse to defending herself) who swung back in turn. [60] Doyle Lancaster then ripped the camera from the hands of Earth First!er Hal Carlstadt, a longtime peace activist (who had picked it up), and then smashed it on the ground, while Logger Larry, who had earlier sped through the blockade in his truck only narrowly missing some small children, smashed the camera lens with his axe. [61]

Now the Lancasters’ anger escalated to the point of deadliness. 21 year old Dave Lancaster, one of their sons who, according to Cherney was not only drunk, but also “high on crank” became hysterical and then punched Hill twice in the face, fracturing her nose in the process. [62] The younger Lancaster alternately laughed and screamed as he pushed demonstrators off of the road. He then drew a shotgun from his pickup truck [63] and shouted “YOU FUCKING COMMIE HIPPIES! I’LL SHOOT YOU ALL!” [64] The elder Lancaster disarmed his son and handed the gun to another employee. [65] At that moment Greg King, who was late again, arrived with a camera of his own and attempted to photograph the goings on. That act riled up the Lancasters even further. Logger Larry hit one of the locals over the head with a piece of firewood. [66] Then, Doyle Lancaster’s other younger son managed to get hold of the shotgun and fired it into the air, also threatening to shoot all of the “commie hippies”. [67]

At long last, law enforcement finally arrived. Mendocino County Deputies, Humboldt County Sheriffs, and California Highway Patrol officers all converged at once. They quickly determined that the Mendocino County deputies, based in Willits (more than 90 minutes away by any suitable means of transportation) had jurisdiction. [68] Once that matter was settled, they took statements from the Lancasters but refused to take testimony from Mem Hill who was the primary victim of the altercation. [69] Greg King asked one of the deputies to take action, who responded that the road was “private, nothing I can do,” which was a lie, as the road was actually publically funded. King continued to press the matter asking, “what if Lancaster keeps his promise and shoots me?” to which the deputy responded, “I can’t predict the future.” [70] Dave Lancaster was later spotted that night, stalking up and down the road still brandishing his shotgun. [71]

To numerous environmentalists and witnesses present, the disinterest shown to the activists by the law enforcement agents was clearly biased against the demonstrators. Darryl Cherney specifically declared, “(The Lancasters) are going to have the heck sued out of them. Here you have these big tough logger men who say they care about people , but look who’s punching out women, driving their logging trucks at breakneck speed past children. We’re finding out who really cares.” [72] Judi Bari echoed these sentiments, explaining, “I don’t want them to think it’s open season on Earth First!ers because it’s not. We’re not going to tolerate this kind of violence.” [73]

However, Cherney was to be greatly disappointed. The Mendocino County deputies directed Greg King and Mem Hill to the Sheriff’s Department in Willits. King demurred, but Hill pursued the matter. Once there, Sergeant Stapleton informed her that the matter was out of their jurisdiction, since it had taken place in CDF property. Hill was then instructed to return to Whitethorn and make her complaint with the nearest CDF ranger, assuming she could find one. She couldn’t [74]

The Sheriff’s Department and Mendocino County District Attorney’s Office then issued a one-sided press release (based on the Lancaster’s statements and the clear omission of any contradictory evidence from those attacked by them) blaming the victims, but failing to elaborate on how Hill’s nose got broken, and DA Susan Massini refused to prosecute. Eighteen of the demonstrators, including Bari, Cherney, Hill, and King signed an open letter to the DA stating that they were appalled at her decision, even though they had submitted photos, statements, and a broken camera as evidence. The letter concluded by asking, what would have happened had an Earth First!er punched a logger, broken their nose and their camera, and threatened them with a shotgun instead? [75]

The Ukiah Daily Journal ostensibly excoriated both the Lancasters and the demonstrators (acting as though all of them were associated with Earth First, which wasn’t true), specifically singling out the protesters for “bringing their children with them,” as if shielding the latter from the real world was the best way to solve the problem. [76] It evidently never occurred to the editors that perhaps the children lived there and had been present, because their home was being threatened by a reckless and ship-shod logging operation. It was apparent to many of the demonstrators that the local authorities and press were taking their marching orders from Corporate Timber. [77]

* * * * *

The media had covered National Tree Sit Week fairly extensively, but they were most interested in the hearings on the spotted owl. The timber companies knew this, and made sure they were well represented in Redding on August 17 by their dozens of front groups and several thousand gyppo contractors. [78] Careful observers noted, however, that the vast majority of spokespeople present were mostly culled from the ranks of management. [79] What workers were present had been given a day’s wages, bussed in, and provided with premade signs and packets full of talking points. [80] L-P had done their part. One week before the hearings, they mailed a letter to all of their employees urging them to travel to Redding, and informed them they would be shutting down their mills on that day. “We are convinced that the spotted owl is not threatened and that this is a blatant attempt to stop logging,” said part of the letter. The company provided yellow ribbons to all that attended the hearing. [81] Some signs (including those made by P-L) read “Pals of the Owls: Trees are America’s Renewable Resource” and “Trees, Jobs, and Owls” [82]—sentiments that, divorced from the Corporate Timber rhetoric, environmentalists would likely have endorsed in the right context. However, others read, “Preserve the Spotted Owl—Stuff it”, “I Like Spotted Owls Fried in Exxon Oil”, and “Spotted Owl: Tastes Just Like Chicken”, which betrayed the event’s vigilante mob character. [83]

It was because of that atmosphere (as well as National Tree Sit Week) that Earth First!ers chose to boycott the hearing. “I think there’s a real danger of violence because of some of the rhetoric the timber industry is using,” said Betty Ball, who had recommended that members of the Mendocino Environmental Center stay away. Darryl Cherney was even more direct, opining, “It’s going to be a big owl bashing circus, with people justifying the extinction of a species and destruction of our forests so they can have an extra year’s worth of work.” [84] He added,

“Anyone who wants to can put their thoughts on paper. There’s no reason to go up against 5,000 angry people. We’re not trying to save (just) a bird. We’re trying to save the forest and the planet. The Spotted Owl is an indicator species, which means if it is extinct then the health of the forest, and jobs, are at stake.” [85]

Before the hearings began at 1 PM, the timber industry staged a huge rally, attended by as many as 3,000 yellow shirted people, outside of the hearing site at the Redding Civic Auditorium in 100 degree heat. Bill Dennison, the Christian fundamentalist president of the Timber Association of California (TAC) declared, “We’re going to fight, and we’re going to win!” to the roaring crowd. [86]

Another one of the keynote speakers was Anna Sparks. Dressed from head to toe in yellow and wielding a chainsaw, standing from the makeshift stage on top of a flatbed truck, Sparks (as usual) gave a speech replete with Corporate Timber talking points, opining:

“You are seeing the silent majority come alive and tell their government we pay its taxes, we give you homes, we supply your computer paper, and your toilet paper. This is not a Northern California problem. This is a Los Angeles problem, because when we cannot cut trees we cannot give them homes; we cannot give our grandchildren homes in Oregon, Washington, or California, where we have to cut timber for New York City, Chicago, for those areas that desperately need homes…

“Do not list the northern spotted owl as threatened. Do not list all the species they are going to bring up and throw at you, using our system that protects our country, that protects our environment. Do not use the system against us to put us out of the very business that supports the necessities of life. We can grow timber forever if we manage that timber properly, and we have been doing that since Christ walked on the earth.” [87]

The huge crowd applauded and cheered loudly. After the standing ovation, Sparks was followed by Republican State Senator John Doolittle, who declared:

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are fighting a well-organized, very powerful, and very tiny political movement. Today we have begun to fight by marshaling the rank-and-file of these communities, who live here, who work here, who depend upon preserving the quality the environment, so that all the varied uses of the forests can occur.

“We have to stand up and be forceful in asserting our rights. After all, we have the government of the people, for the people, and by the people. We can coexist with the spotted owl. We are not against the spotted owl. In fact, this animal is flourishing as the studies have shown. These facts should lead to the conclusion to remove the owl from even the ‘sensitive’ designation. It is not threatened; indeed it is prospering.

“You and I know that after this issue is settled, there will be a snail darter, or a horned toad, or something else that will come along that will be the new justification to stop you in exercising your God-given right to liberty and to the pursuit of happiness…

“We outnumber this little group 1,000 to one. The people we are up against call themselves environmentalists. We love the trees. We love the fresh air. We love the scenic wonders of this magnificent land, so we want to make sure the best is protected.

“Over the years we have had the concept of multiple use of our federal lands. Now this concept is being attacked by far left-wing individuals who have a totally different objective in mind than simply protecting the environment…

“We should be angry; we should be focused, and we should be effective. It will begin today…as a great hero of mine once said, ‘There is no substitute for victory. Go for it and seize the colors!’” [88]

Doolittle may have been quoting the words of General Douglas MacArthur, but he was channeling the organizers of witch hunts of old, and all of his statements were the familiar Corporate Timber talking points. US Congressman Wally Herger, a Republican representing the Sacramento Valley, offered similar thoughts. [89]

During the hearing, Corporate Timber again attempted to make their case against that the spotted owl could exist in managed second and later growth forests. Speaker after speaker, most of them affiliated with the Timber Association of California (TAC), a Corporate Timber lobbying organization, claimed to have conducted independent studies with results contradicting the findings of the FWS. Linwood Smith, a self described independent consultant and wildlife biologist began:

“There are problems with using old-growth studies as the foundation for listing (the spotted owl as endangered). The data we have (is) in direct conflict with the FWS’s data. Given the TAC’s data, which are so contrary to the listing, a listing of the spotted owl as threatened is premature. We strongly recommend the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service postpone the listing until additional studies can be conducted in northwestern California, particularly so we can learn more about reproductive biology, demography, and other features that are critical to our understanding of what needs to be known before a listing can be made.” [90]

Smith was followed by Steven Self, another wildlife biologist aligned with TAC, who gave a similar testimony:

“Our study focuses on large tracts of extensively managed young-growth stands in a variety of habitat types. In fact the only habitat type we did not include was old growth…Of the 29 areas surveyed, we found owls using 26. Our data indicates all 29 areas are used by spotted owls. Most of the owl sites we checked contained pairs of owls. We found baby owls in many of our study areas located throughout the range of our survey. We found owls using managed young-growth forests including hardwood, prairie-forest mix, even-aged and uneven-aged.

“We found areas with two to three times as many owls as have been found in old-growth forests in Washington. If we had completed our study as the Forest Service does (its) monitoring, we would have missed many pairs of owls and a number of sites with baby owls…

“Why has no one looked where we looked? Even better, why has data developed in old-growth forest types in Oregon and Washington been used to predict that owls will not use another unsurveyed habitat type, that of our managed young growth forests?”

“(This) appears to be misleading at best and categorically wrong at worst.” [91]

L-P’s chief forester Chris Rowney cited a (not peer reviewed) study on 500,000 acres of Mendocino County timberland that allegedly found two-dozen owls nesting in cut-over land where they should not have been found. Georgia-Pacific forester Travis Huntley declared that owls had been found in “every timber type, including young trees not even ready for logging.” [92] Representatives from Sierra Pacific Industries and Pacific Lumber gave similar testimonies while various gyppos and small mill owners warned of certain job losses should the owl be listed. [93]

There were few environmentalists on hand to challenge the barrage of Corporate Timber propaganda. Many had indeed stayed away, due to the mob hysteria. [94] Lynn Ryan questioned the inherent conflict of interest in the industry conducting its own surveys on the spotted owl, declaring, “I hope these studies are unbiased. I am happy to hear the owl is as healthy (as reported); however, I remain suspicious…The more I learned the experts didn’t know about the spotted owl. The information (presented by the industry) is almost unbelievable.”

Tim McKay likewise declared,

“Only legislation can stabilize the Forest-Service timber sale program. That legislation—whatever it might be—cannot pass into law unless environmental interests win some major concessions to ensure protection for the biological function of the forest environment.

“All of the yellow ribbons and all of the yellow ribbon men and women (wear) cannot put the forest policy status quo back together again. What is needed is a climate of mutual respect, if there is to be a resolution to this issue. But the climate only seems to be getting hotter. Remember there are millions of people out there who are watching, who think their national forests are being preserved for their scenery and wildlife. What will they think about all of this?” [95]

The hearing concluded with neither the “workers” nor the environmentalists achieving any sort of meaningful resolution, and the debate would rage on hotter than ever. Meanwhile, Earth First! continued National Tree Sit Week.

* * * * *

The climactic action of national Tree Sit Week took place on the ground at an L-P cut near the second Mendocino County tree sit on August 18, 1989 near Albion, California. In the early morning, a crew of Gyppo loggers had entered the forest to work, quite unaware that dozens of activists lay in wait until the former had passed on. Then they made their move. A sign by the road labeled “Demonstration Forest” was altered to read “Devastation Forest”, and below that was spray-painted Harry Merlo’s already infamous “we log to infinity” quotation. At 8 AM, company security realized that the woods had been occupied, and raced to the scene, where a dozen demonstrators had blockaded a logging truck. The driver at first demanded, and then pleaded that he be allowed to proceed to no avail. Realizing that he had no alternative, he reversed course, only to attempt an alternate traverse into the forest by way of a spur, but he was too late. Two Earth First!ers anticipating his actions had quickly rushed to the spur and had hastily assembled a slash blockade. [96]

The angry driver alighted from his cab and went to work dismantling the blockade, while the demonstrators watched from a fair distance away. Upon completing his task, the driver returned to his cab, gunned the motor and lurched forward, but not before one of the demonstrators closed a metal logging road gate again barring the driver’s access. The livid driver once again halted abruptly, opened the gate, and then sped away in a fury. His apparent destination was the Calpella Chip Mill, and the apparent fate of the load of pecker poles he was carrying was waferboard. [97]

Reinforcements arrived for the protesters as did additional forces for the County Sheriffs, led by Deputy Keith Squires, as well as a private L-P security guard. As they were huddling, Hal Carlstadt attempted to blockade an L-P service truck only to find himself grabbed by Squires and quickly thrust into the back of a police car, and hauled away. [98] This diversion allowed the remaining protestors to again close the gate and, this time, padlock it shut. This act halted a second logging truck for some time, until an L-P crew arrived and removed the lock with an acetylene torch; the truck proceeded through the once again opened gate. [99]

Additional deputies arrived on scene and surrounded the gate to prevent any further closures. A third truck loaded with pecker poles arrived, driven by a 39 year old man from Boonville named Donald Blake. The demonstrators moved to intercept, and the police attempted to thwart them. Thus distracted, the sheriffs didn’t notice Judi Bari slowly driving a battered old derelict car into the truck’s path. Once there, she quickly shifted gears into park, set the parking break, and locked the doors just as the police dispersed the crowd. While the dumbstruck sheriffs scrambled to regain control of the scene, Sequoia, adorned in a giant spotted owl costume ascended to the roof of the car and danced merrily about hooting and warbling. [100] “You’re not taking very good care of my babies” she sang as the L-P crew looked on, helplessly. [101] The Police were unable to dislodge the car from its spot until a tow truck was summoned for the task. The impatient logging truck driver, however, managed to negotiate his way around the blockade with some difficulty. At this point, the Earth First!ers and their allies had emptied their truck blockading bag of tricks, so they abandoned the gate and attended to the tree sitters. [102]

* * * * *

The week of events had, so far, stirred up quite a range of reactions. Although they were actually combined efforts of many groups—not just Earth First!—the latter got much of the credit and, for that matter, much of the blame. [103] Some of the deputies were sympathetic to the demonstrators, however, and at least one Parks and Recreation ranger wished Earth First! well, admitting that G-P’s and L-P’s greed was destroying the forests and the lives of those living in the county. [104] Not all of the log truck drivers that passed by were hostile either; some even blasted their horns in apparent support for the tree sitters. Several demonstrators also distributed leaflets highlighting the issue to interested motorists, some of whom engaged in friendly discussion (and sometimes debate) with the former. One leafleter repeatedly emphasized, “We’re not against loggers...we’re only against what big corporations are doing to the woods. Clearcutting is clearcutting jobs, too.” [105] Passersby stopped to deliver encouragement and material aid to the tree sitters, and even the local press was less hostile than usual. [106] Even before the week of action took place, falsified leaflets and press releases designed to discredit Earth First! referred to “National Tree Shit Week” were distributed in both Humboldt and Mendocino Counties. These were latter determined to be the work of Candace Boak and her associates in WECARE and Mother’s Watch. More overtly, embattled IWA Local #3-469 official Don Nelson already facing snowballing scrutiny from his rank and file attempted to deflect the blame to Earth First!. In an open letter, Nelson angrily declared:

“Tree sitters and tree spikers are not environmentalists. They contribute nothing to serious debate or negotiations over the Forest Practice issue. Organized labor cannot support or endorse their actions because what they do and what they advocate is illegal and dangerous to themselves and puts woods and mill employees in dangerous situations…Tree sitters should be prosecuted like any other trespasser.” [107]

Greg King angrily responded, “Not only do we ‘contribute’ to current timber debate, but we have for the past three years helped define its parameters. Also, to lump tree-sitting and tree-spiking as one is inaccurate, unproductive and endangers our people.” [108]

Darryl Cherney likewise retorted:

“Perhaps (Don Nelson) should change the name over (his) door from I.W.A. to G-P. When (he comes) down from off of the fence (he) should be coming down on the workers’ side, not G-P’s. And since (he) supposedly represents the workers in negotiations with G-P coming down on the company’s side represents a true conflict of interest. Of course, after (he) sold out the contract, we all figured whose side (he was) on. This just confirms it. Also, regarding sitting and spiking: anyone in a position such as (his) who would lump those together is engaging in linguistic terrorism, not to mention endangering our sitters.” [109]

Don Nelson, who had once led a join picket with environmentalists against L-P And who had spoken out against the Maxxam takeover of Pacific Lumber was now expressing opinions scarcely different from Glenn Simmons, who sneeringly opined:

“As reporters we often refer to the ‘tree-sitters’ as environmentalists, but that is a misnomer, because a true environmentalist is a person who works to solve environmental problems in a constructive manner, including reasonable dialog.

“There are many environmentalists, from all walks of life, who are thoughtful, caring, and realistic. They may disagree over clearcutting, or some other environmental issue, but they are not extremists.

“Extremists such as those who protested in Dan Hauser’s front yard and who even climbed a tree in it, are those who use excessive, unconventional, drastic, harsh and radical means to get their point-of-view across to middle America.

“About the only way to attract attention when you belong to an organization such as Earth First!, is to act in the extreme—similar to a child acting out to receive attention.” [110]

Nowhere, not once, in Simmons editorial, did he issue so much as one condemnation of the Lancasters in the following issues after the loggers had acted out their frustrations. Evidently, only environmentalists who challenged Corporate Timber were “spoiled brats”.

In spite of these condemnations, it would soon be proven, once again, that it was not the Earth First!ers and their allies who were the actual spoiled brats or even terrorists. There was one more demonstration during National Tree Sit Week on Sunday afternoon, August 20, 1989, at the Georgia-Pacific Mill in Fort Bragg. The company had anticipated the action and shut down for two hours before the approximately 100 protesters assembled and marched down the main thoroughfare through town until the police dispersed the crowd. [111] Other than that, the demonstration itself was uneventful, though it was what didn’t happen there and what did happen elsewhere that was of greater significance. [112]

* * * * *

Participants at the Fort Bragg rally couldn’t help but notice that Judi Bari, Darryl Cherney, and Sonoma County Earth First!er and IWW member Pam Davis, who had been expected to join in, never arrived. The three had been en route to Fort Bragg along with Bari’s daughters, Lisa and Jessica, and Davis’ two sons, Nicholas and Ian. [113] They were passing through the Anderson Valley town of Philo near Lemon’s Market when they were hit from behind by trucker Donnie Blake, still upset about being blockaded less than 24 hours previously. [114] The impact shoved Bari’s vehicle into a nearby parked car, which was in turn shoved into a nearby restaurant. [115] All of the occupants survived, albeit banged up, suffering concussions, whiplash, and abrasions, but Bari’s car itself was totaled. Bari suffered a mild concussion and one of her daughters suffered facial lacerations from shards of the broken window glass. [116] Pam Davis meanwhile suffered a broken bone in her right hand. [117] According to Darryl Cherney, in a twist of sheer irony, the parked, second vehicle belonged to Fish and Wildlife researcher Kevin James who was having lunch in the restaurant with G-P seasonal biologist John Ambrose before heading out to conduct a study on the Spotted Owl. [118] Judi Bari would later quip, “(The incident is) the whole struggle in a nutshell.” [119]

It was uncertain at first whether or not Blake had hit the activists accidentally. According to the police report, Blake had been aware that he had been following Bari’s car (a 1979 Mazda wagon) for about ten miles before the crash. The posted speed limit was 30 MPH, and there had been pedestrians in the vicinity, whom Blake later claimed had distracted his attention. However, two eyewitnesses—the first, Jean Warsing, an employee of the market who was outside pumping gasoline for the second, a man identified solely as “McCutheon”—placed Bari’s speed at 25 MPH and Blake’s at 45. Both recounted that Blake had showed no signs of slowing down. At first Bari was convinced that the driver had no malicious intent, declaring, “I didn’t think at the time (that) Donnie Blake hit us on purpose. He had a kind face.” [120] She also believed that without a doubt the driver had been remorseful and upset. [121] When the victims were being treated by paramedics, however, a visibly disturbed Blake told Bari, “The children, I didn’t see the children!” which should have clued her in that he had not simply hit them accidentally. [122]

Several months later, Bari later determined that Blake’s actions were indeed deliberate and retaliatory. Bari recounted, “The truck was not tailgating, and he hit me without warning. There was no sound of horn or brakes.” Blake claimed he hadn’t seen Bari’s car in front of him, and estimated his speed at 45 MPH, but he also admitted he was aware that he had a broken speedometer. However, the California Highway Patrol did not test Blake for drugs, question him about his motives, or even give him a fix-it ticket for his speedometer. They instead went to the junkyard to test the brake lights on Bari’s wrecked vehicle (which worked), and then came to the hospital and questioned Bari about the brake lights anyway while the latter struggled to remain conscious. Everyone recovered, but Bari was angry, stating, “I was clearly the victim of this incident…this was no investigation, it was blatant harassment…There’s no protection of the law for Earth First!ers in Mendocino County.” [123]

* * * * *

Meanwhile, back in Fort Bragg, word of the accident reached the demonstrators. In lieu of Judi Bari’s keynote speech, Don Lipmanson read the prepared statement that Bari had intended to give. In response to Don Nelson’s asinine comments about tree sitters not being “real environmentalists”, she had retorted,

“If Don Nelson were a real labor representative, he’d be up in the trees with the environmentalists because…jobs are falling along with the trees… [124]

“Workers issues are the same as the environmentalists. We are interested in long-term sustained yield logging. I’m a carpenter and I live in a wood house. I would like to continue using wood…I look forward to the day when the loggers and the millworkers will join us on the line.” [125]

Lipmanson concluded that Bari, Cherney, Davis, and the children had been victims of, “too many logging trucks going too fast to get all of the timber they can,” evidently ignorant of Blake’s deliberate actions. [126] This was not to be the end of the heated tensions, however.

Two weeks after the Redding rally, as two tourists—who had nothing directly to do with any of these incidents or events—were taking a canoe trip along Big River near Whitethorn on the northern Mendocino Coast, they were bullied by gyppo loggers when the former had chanced upon a nasty looking clearcut and had attempted to photographically document the scene. [127] Glenn Simmons had nothing to say about that either, but issued yet another “immature brat” condemnation of Earth First! in response to Mike Roselle criticizing the events in Redding as a “media circus”. [128] While Earth First!ers were willing to give the workers the benefit of the doubt, the industry by contrast had whipped up many of their supporters into a state of kneejerk hair trigger alert.

* * * * *

Clearly Corporate Timber was dragging the environmental movement through the mud, and enough was enough as far as Anderson Valley Advertiser journalist Crawdad Nelson was concerned. He had already vented his spleen in bitterness over the actions of his father and the capitulation by the IWA rank and file to the union officialdom’s collaborationism, and now he was furious. [129] Rob Anderson, Anderson Valley Advertiser editor and publisher Bruce Anderson’s younger brother, was no less bitter. [130] Both of the writers were ex-millworkers and currently sympathetic to Earth First!, if not full blown advocates of the latter. Both questioned whether workers could ever take a stand against corporate logging, and Rob Anderson even questioned whether logging was “a noble profession.” Such pessimism towards the timber workers in general—which at times bordered on condescending and should have more properly been directed at Corporate Timber’s front groups—did not sit well with Mike Koepf, who had resigned from the publication over unrelated personal disputes with editor Bruce Anderson (who did not share Nelson’s or his brother’s pessimism towards timber workers), and Judi Bari. [131] The controversy that had raged one year previously within the ranks of the IWW was taking place in northwestern California. A heated debate ensued within the pages of that publication which lasted several weeks.

Crawdad Nelson was especially incensed that the IWA Local #3-469 office sported signs reading “Save a Logger, Eat an Owl” [132], while Rob Anderson was especially disgusted with Don Nelson’s letter equating tree sitting with tree spiking and calling both “terrorism”. Both proceeded to excoriate the leadership of the IWA and business unions in general for capitulating to the red-baiting and class collaborationism. [133] Bari certainly agreed with the criticism of business union leadership, and the pro-capitalist orientation of the AFL-CIO, stating:

“There’s a saying that came out in the 50’s about unions, which says that once unions cut off their left wing, they’ve been flying in circles ever since. These unions have acknowledged management rights which give them no say over the point of production, such as the destruction of the forest, which the workers need for their survival. They have confined themselves to wages and benefits which have made them ineffective.” [134]

Rob Anderson had said, eerily echoing Dave Foreman and Roger Featherstone, “the only real difference we can see between Don Nelson and his workers and Harry Merlo, Charles Hurwitz, and G-P President, T. Marshall Hahn. [135] Bari responded by pointing out that Nelson was not representative of his rank & file, and that the difference between Merlo (or Hahn) and the workers was that the latter were not in charge and didn’t yet have the organized economic power to resist. She hinted, however, that as an IWW representative, she had contacts in the industry, but obviously didn’t name them in order to protect their security. [136]

Bari wasn’t bluffing. As early as June 1989, She and Darryl Cherney were in regular contact with former and current Pacific Lumber workers Kelly Bettiga, Pete Kayes, John Maurer, Lester Reynolds, and others. Although the ESOP campaign was unraveling, at least some of the workers were not willing to give in without a fight. Pacific Lumber, like many corporate entities published a company newsletter, in this case called Timberline, vetted by Maxxam, of course, which presented a saccharine and sanitized view of current working conditions at Pacific Lumber. For example, the April 1989 issue of Timberline announced the promotion of John Campbell to P-L President and the ironically but coincidentally named Thomas B. Malarkey to the position of Vice Chairman. [137] Other articles marked the length of some workers’ service to the company, discussed various awards, announced retirements, and one photo essay described life in Scotia in 1917. The banner headline was superimposed on a silhouette of a redwood forest; immediately to its left was the word “PALCO” written vertically; a subheading read, “Published by and for the employees of the Pacific Lumber Company.” The publication was a complete façade, designed to give the appearance that the company was one big happy family.

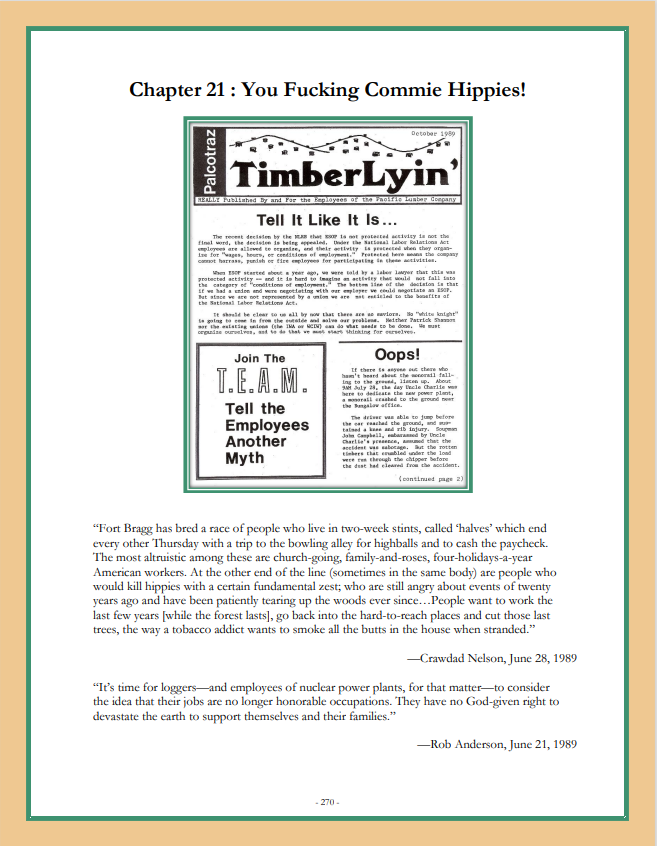

Nothing could be further from the truth, of course. Bettiga, Kayes, Maurer, and Reynolds responded by publishing a newsletter of their own, called Timberlyin’ which featured all of the news not covered in the official company publication, such as the 60-hour workweeks, the rip off of the workers’ pension fund, various broken promises made by Maxxam, updates on the ESOP campaign, and ecological issues, because—despite Crawdad Nelson’s and Ron Anderson’s pessimism, these workers at least, did have a vision which extended beyond their bank accounts. [138] Timberlyin’ resembled Timberline quite closely, except that the word “Palcotraz” (an obvious reference to the old federal prison on Alcatraz Island) took the place of Palco, the banner graphic depicted a clearcut hillside covered with stumps, and the subheading read, “Really published by and for the employees of the Pacific Lumber Company.” [139]

If the underground publication had a familiar ring to it, it should, because it was essentially the same tactic used by Bari and her coworkers during their struggles in the Washington Bulk Mail facility in the 1970s. In every respect, Timberlyin’ was exactly like Postal Strife. Judi Bari and Darryl Cherney were also contributors to this publication [140];, and Kayes and the others distributed it in Scotia, Rio Dell, Carlotta, and Fortuna. [141] They published a second issue in October 1989, which featured updates on the ESOP campaign [142], skewered the company’s health plan [143], reported on the monorail incident—which was apparently quite an embarrassing moment for John Campbell and Charles Hurwitz [144], and again took issue with Maxxam’s unsustainable logging practices. [145] It’s difficult to say for sure who wrote exactly what, though Cherney recalls that each of the workers, plus himself and Bari collaborated more or less equally on the project. [146] Like Postal Strife, Timberlyin’ was irreverent, referring to Hurwitz as “Uncle Charlie” for example, and it generated both positive and negative responses among the P-L workers (as was evidenced by short letters to the editor in the second issue).

Kayes, Maurer, and Reynolds also remained active with the Pacific Lumber Rescue Fund which helped a group of P-L workers, retirees, and their spouses file a lawsuit in federal court against Maxxam, Executive Life, the old Pacific Lumber Board of Directors, and others to protect their pensions. The plaintiffs were worried about their pension fund and were deeply concerned about how Maxxam had used it, most certainly illegally to facilitated the takeover of Pacific Lumber in 1986. They were convinced that they had been given an unfair deal because the annuity provided by Executive Life was not guaranteed by any state or federal agency, and it lacked periodic cost of living increases. Because Executive Life was highly invested in high risk junk bonds, this did not inspire confidence in the plaintiffs that their pension had any real security. [147] In light of the previous setbacks experienced by these workers, including the stillborn IWA organizing efforts and the failed ESOP campaign combined with the constant threat of retaliation by Maxxam, that these workers were willing to continue speaking out at all was indicative of much larger possibilities.

Nevertheless, Rob Anderson had argued that workers on a small scale, passing information to Bari on the sly, while a welcome development, was hardly an expression of mass, collective working class power. This is technically true, but, given the relative weakness of the working class in the closing months of the 1980s—especially given world events, including the fall of the Berlin Wall and impending collapse of the Soviet Union, which many accepted as a vindication of capitalism—this was at least something. Many, including Anderson and Nelson, doubted that workers would ever challenge capital on a large scale beyond narrow bread and butter issues. Those doubts were unfounded, however, because clear across the country, it was happening among the miners in Appalachia.

* * * * *

On the opposite coast, in Kentucky, southwest Virginia, and southern West Virginia, beginning on April 5, 1989, 1,500 members of the United Mineworkers of America (UMWA) had been on strike against the Pittston Coal Company. The strike had escalated to the point where rank and file workers as well as local and international union officials were engaged in militant direct action and sabotage exceeding anything yet done by Earth First!. [148] Paul Douglas, the Pittston CEO whose annual salary averaged $625,000 had made demands of concessions that would have effectively crushed the UMWA. Along with Pittston President, Michael Odom, Douglas was essentially attempting to duplicate the efforts of Harry Merlo and lead a charge to eradicate unions within the coal mining industry. To the miners of Appalachia, the union was more than their livelihoods, it was their whole cultural existence—as sacred as the Baptist Church. Odom had declared that the workers’ unwillingness to slit their own collective throats as being “out of step with reality,” presuming that reality meant perpetual austerity and worsening conditions for workers whose job was one of the most dangerous in the world, perhaps even more so than the timber workers. [149]

By August, 1989, even before National Tree Sit Week, the battle in Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia had literally escalated to the point of war. Mass pickets of the mines and mining facilities had been thwarted by injunctions, limiting the number of pickets to six. That the judicial system and the governor of Virginia, Gerald Baliles—who had received $265,000 in campaign contribution from the coal operators in the state, plus the use of the latter’s private luxury planes and helicopters for campaign purposes—were in the company’s pocket was of no small consequence. The governor had opposed severance taxes and had provided over 500 state police to the company to help break the strike. A judge also levied almost $4.5 million in fines against the union for what he described as “acts of terror”, including threatening and assaulting scabs in the coalfields. [150]As if this weren’t enough, the company had recruited scabs from far and wide, including from the Assets Protection Team, made up of less than savory, heavily armed, extreme right wing mercenaries recruited through Soldier of Fortune and other similar publications. [151]

Desperate to protect their way of life, miners had turned to direct action, including denting and shooting at scab trucks and breaking their windshields, digging trenches to block access roads, using jack rocks (caltrops, sometimes referred to as “mountain spiders”), dropping power lines, and even blowing up buildings and equipment with dynamite in one instance or another. The miners, decked out in camouflage, were doing much of this under the cover of darkness, but they had the near complete solidarity of their families, friends, neighbors, and community, and they were not alone. [152] The strike spread beyond merely the Pittston Coal Company. Pittston subsidiary, Elkay Mining Company had gone as far to bring in a two professional scab operations in succession (the first went bankrupt and was replaced with a second company known as “Con-serv, Inc.”) after workers there engaged in wildcat strikes in July. When A.T. Massey Coal Company reopened their Rum Creek mine, the strike spread to all of Massey’s nonunion operations. By September, with the help of the UMWA, union and nonunion workers began engaging in direct action tactics, including building barriers—some of them constructed of old tires, railroad ties, and even a soggy abandoned couch—to keep scabs out of the struck mines [153]

The strike affected the whole region. Most of the local businesses, much of whom displayed “We support the UMWA” signs in their windows refused to transact business with the scabs. [154] The workers and their families dressed in camouflage, down to their underwear and babies’ diapers as a gesture of unity. They had each others’ backs, especially when faced with police investigations into their use of direct action, including jack rocks. On Sunday, September 17, 1989, 98 miners, supported by thousands of allies, carried out an occupation of the Moss #3 Preparation Plant, and escorted thirteen scabs out of the facility. [155] The miners were sporting yellow ribbons, which so commonly in the timber industry signified solidarity with the employer, but in this case symbolized working class solidarity and class struggle. Workers repeatedly talked of “defying the laws”, “filling the jails”, and “general strikes”. They called their camp, Camp Solidarity, both in reference to the principle that binds the working class as well as the Polish Solidarity movement. White miners in southern Virginia, a state once steadfastly loyal to the Confederacy and the Jim Crow era that followed declared, “Blacks work underground with us. They are our brothers.” It was not surprising to discover, then, that the president of this particular UMWA local, who was dressed in camouflage himself, and joining his brothers and sisters in the trenches, was black. [156]

Union solidarity poured in from around the world. Gary Cox, an oilfield worker himself, and a handful of other IWW members (including Darryl Cherney), at various times in the late summer joined miners from Virginia, West Virginia, Alabama, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, and Ohio, as well as groups of auto workers from Chicago and Detroit, groups of steel workers from Pennsylvania and Tennessee, Teamsters from New York City, Communication Workers from all of New York State, and various unions from Boston. [157] In early September, 10,000 strikers and supporters gathered for one of the largest union rallies held in Appalachia ever, which featured Jesse Jackson and UMWA President Richard Trumka. During his speech, Jesse Jackson singled out Republican administrations for creating such an anti-union atmosphere, declaring, “During the past ten years, political leaders such as President George Bush have used the American flag to pull the wool over our eyes.” [158]

Miners also looked past the official ideologies of anti-communism. One of them declared, “Nicaragua (referring to the Sandinistas) is just another workers’ struggle. They are fighting for better living conditions, just like us, and just like us, the U.S. government is trying to break their strike.” Even the officials were at least parroting the militant words of the rank and file. Cecil Roberts, the Executive Vice President of the UMWA himself stated, in a speech given at a rally at Camp Solidarity on August 2, 1989, “We are not dealing with a misguided company, we are dealing with a rotten system.” He went on to describe the Wagner Act as a cooptation of working class revolt and if the bosses wanted a working class revolt, the miners were more than willing to give them one. [159] Despite crushing legal fees, brutal repression, and company intransigence, the workers’ militancy was having an effect. Production was down anywhere from 50 – 67 percent. [160]

It was understandable that many, including Rob Anderson and Crawdad Nelson would not have believed workers revolting on such a mass scale was possible, but there they were. It was as though the miners had taken several pages out of IWW history books, not to mention a handful of paragraphs from Ecodefense, though in truth, typically such tactics develop directly from the workers’ experiences and struggles. Few in America heard about the struggle, except in the pages of the alternate press [161], though CBS’ 48 Hours did film picketers being arrested and hauled to jail in school buses. [162] If the revolt had spread, there’s no telling what would have happened or which industries it might have affected.

Sadly, as it had happened so many other times in so many other struggles, the union bureaucrats eventually capitulated to the bosses, agreeing to concessions, but calling that a “victory” (because the final results were not nearly as bad as the company’s original draconian demands—which was probably by design). No doubt the international leadership of the UMWA feared rank & file militancy and control and moved to crush it lest it spread out of control. [163] At least the G-P millworkers knew how that felt. It would take something other than the AFL-CIO to win such a struggle.

To Judi Bari and her comrades, this seemed all too natural. This was a job for the likes of the IWW, and she decided to take another page from IWW history and called for outside help. First she and a number of other Local 1 members attended the IWW’s annual convention and reported thoroughly on the situation on the North Coast.[164]; Then, following that, she wrote an article for the IWW’s official monthly publication, the Industrial Worker, which included the following appeal:

“Historically it was the IWW who broke the stranglehold of the timber barons on the loggers and millworkers in the nineteen teens. The ruling class fought back with brutality, and eventually crushed the IWW (Timber Workers Industrial Union), settling instead for the more cooperative Business Unions. Now the companies are back in total control, only this time they’re taking down not only the workers but the earth as well. This, to me, is what the IWW-Earth First! link is all about.

“If the IWW would like to be more than a historical society, it seems to me that the time is right to organize in timber. This is not to diminish those active locals and organizers who are already involved in workplace struggles elsewhere, but to point out that organizing in basic industry would strengthen us all. We are in the process of starting an IWW branch in northern California, and some of the millworkers are interested in joining already. But the few of us who share these views can’t do it by ourselves, especially since the most prominent of us are known to all timber companies as Earth First!ers and can’t get a job on the inside.

;“Back in the glory days, the IWW used to call on ‘all footloose Wobblies’ to go get jobs in places the IWW was trying to organize. I’d like to make the same appeal now, to come to the Pacific Northwest and work in the mills and woods. Anyone wishing to take on this task should contact me. Please take care to avoid using your identity, home address, or exact plans. Your (IWW membership) number will suffice as identification (which can be verified through the General Office). Remember, this is no game.” [165]